Updated July 2022

The best way to stay healthy is to stay healthy. That means mitigating risk when possible. The current dominant lineage of COVID-19 (Omicron-Next or BA-next) is the most transmissible pathogen ever known. Ever. Seemingly every time there is a large gathering of humans indoors (without masks) for any amount of time, there is a large amount of COVID transmission, and many people will become infected.

Realistically though, everything has opened up and we are out and about competing, traveling and adventuring. As such, we are seeing many athletes traveling and falling ill with a second, third or fourth round of COVID. These COVID infections and re-infections catch many of us by surprise. If and when this happens, how we as athletes and coaches manage the ensuing days will dictate health and performance for the following days, weeks, or months leading to the point where we can safely return to sport.

The primary concern for athletes contracting COVID appears not to be the usual list of symptoms (fever, cough, fatigue, trouble breathing, etc.) but something far more sinister, myocarditis. This inflammation of the heart tissue can send the electrical system that makes your heart work efficiently awry and cause arrhythmias which could be life-threatening. Or “worse,” they could cause damage that results in one being permanently disabled.

Such was the motivation that led to professional sports leagues instigating layered protection for their athletes. These high-value assets performing at the sport’s pinnacle make the entertainment product possible. And they’re human beings with families too, so there’s that.

Professional Leagues and Athletes Leading the Way

Through no small feat of science, technology and a bit of arm-twisting, many sports leagues were able to make it through 2020, leveraging their economic well-being to put athletes back in play. With annual revenue of $9 billion, the NBA was the first to demonstrate that COVID could be tamed with their “Bubble.” It worked, and more importantly, it gave others the confidence to try it themselves.

The 2020 Tour de France (TdF) was the first time since the Spanish Flu that a Grand Tour had been attempted during a public health emergency. Many people doubted the ability of the organizing entity, ASO, to execute a “race bubble” effectively, but they had more than $217 million in reasons to make it successful. As I write this, the 2022 TdF has begun, and the complete lack of rider safety concerning COVID is disappointing.

The UCI lists the primary reason for anti-doping controls are the “protection of the athlete” yet concurrently exposes and compels the athlete to compete with an infectious and multisystem illness. This same illness is known to present symptoms like myocarditis, and the effects of world-class level competition while actively having the disease are unknown. But again, the ASO has hundreds of millions of reasons to ensure the show goes on.

Some easy-to-find literature showcases how the NFL leveraged its $15.26 billion annual revenue to pull off a complete competitive season with only a few interruptions. The thoroughness of the protocols is mind-boggling. In 2020 between Aug. 9 and Nov. 21 (15 weeks), the 11,400 players and staff were administered 623,000 tests, with most being tested six days per week. That’s basically a nose swab with your daily morning coffee.

If someone were to test positive, the NFL would do extensive contact tracing, quarantining (in fancy hotels) and more testing. These protocols saved the NFL season and demonstrated that producing a sporting season with minimal disruptions is possible. This also served as a model that NCAA basketball was able to leverage to give us March Madness in 2021.

When the pandemic began, seemingly decades ago, I provided concise and effective guidance for a coach as they guide an athlete’s return to training following infection with COVID. However, treatment and outcomes are of utmost importance when determining best practices.

Those same professional sporting leagues mentioned above executed an effective return to play/training (RTP) model that included an advanced and extensive cardiac testing protocol. This extensive testing and retesting goal was simple: detect and assess inflammatory heart disease in professional athletes with prior COVID infection and use the established guidelines to safely guide the athletes to return to play.

The outcomes of the RTP protocols were exceptional. Athletes were still infected with COVID, and 1-3% of the athletes developed myocarditis. The outcomes were far from catastrophic other than extended rest. To date, no adverse cardiac events have occurred. Not a single one.

But what is this extensive testing and screening protocol, and how available is it to anyone not active in a professional sports league? Tests include IgG, PCR, Troponin, Electrocardiogram (ECG), Echocardiogram (Echo), Cardiac MRI and Stress Echo.

If you’ve ever had a reason to be involved with any cardiac care, you know that these tests are expensive, time-intensive and not scalable for the general sporting population. In short, this level of care is only possible for these sports leagues because they spend immense resources on the health of their most valuable asset to ensure that those assets stay valuable.

Professional sports leagues combined have billions of dollars of resources at their disposal and an abundance of team health professionals along with advanced medical care. The rest of us live in a reality where waiting for scans takes days, results take weeks and the hospitals are both full and empty at the same time. We should do everything we can to avoid COVID and any potential for cardiac events.

The good news is that while COVID has evolved and the Omicron-Next lineage outcompetes Omicron-Previous, our existing models for safe RTP haven’t changed much other than to reinforce what we knew before.

What Coaches Should NOT Do

Throughout the entire COVID process, a coach should not attempt to insert themselves into the diagnosis process. Furthermore, they should not take it upon themselves to know the clinical presentation or pathophysiology of myocarditis. They should understand cardiovascular signs and symptoms of myocarditis or other cardiac conditions and how they show up in exercise data and perceived exertion. In short, the coach should know when the athlete should cease exercise and be referred to a physician for testing and diagnosis.

Guiding the Comeback from COVID

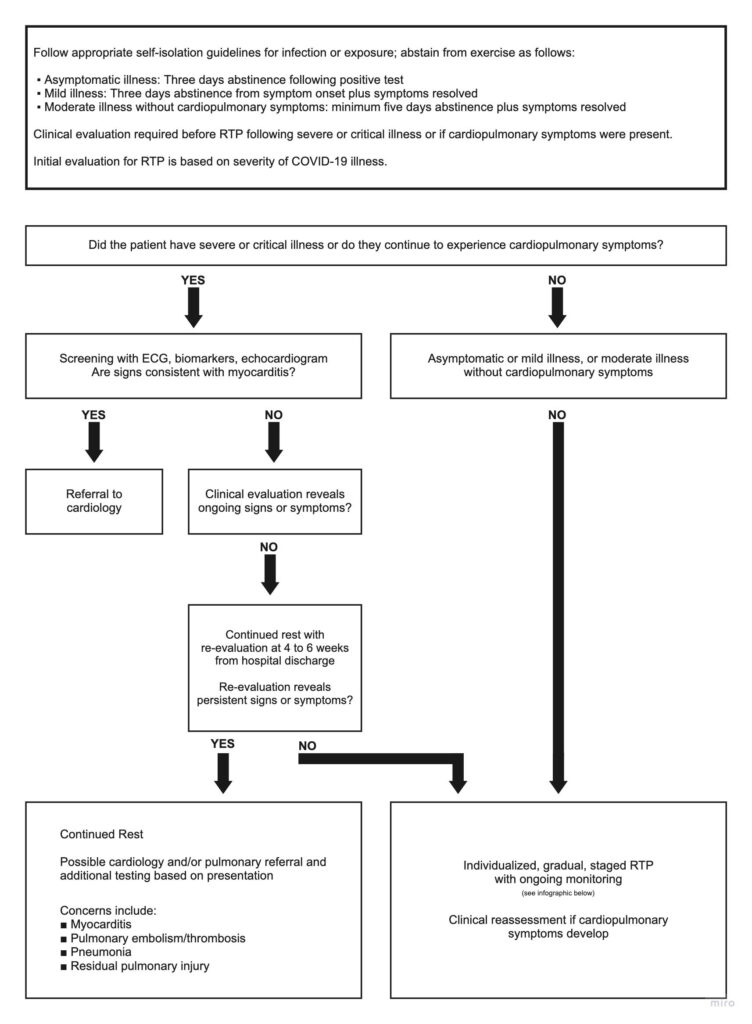

I like the idea of action flow charts in this particular instance. As a coach guiding the athlete, the best thing you can do is keep the athlete informed of the process and what to expect. The RTP process takes weeks or months, not days. The best way to safely RTP is to take the time to follow the protocol.

Start by identifying the severity of the disease, which you can do with this table.

COVID-19 illness severity for RTP screening

| Illness severity | Defining and common clinical findings |

| Asymptomatic | Positive COVID-19 test with no symptoms |

| Minor | Low-grade fever, cough, mild fatigue only, URI symptoms (eg, nasal congestion, sore throat), possibly other symptoms (eg, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anosmia, ageusia) |

| Moderate | Persistent fever (38°C [100.4°F] or higher), persistent fatigue (at least 7 days duration), pneumonia (CXR <50% lung parenchyma involvement), chest pain not associated with cough, activity-limiting dyspnea, orthopnea, edema, palpitations, syncope |

| Severe | Dyspnea, hypoxia (SpO2 <94% on room air), need for supplemental oxygen, CXR infiltrates involving >50% lung parenchyma, requiring hospitalization for medical treatment |

| Critical | Respiratory failure (ie, mechanical ventilation, ECLS), shock, multiorgan dysfunction |

“Moderate illness” indicates a different action compared to lesser disease states, and more severe than moderate places the athlete in the hospital.

Next, we move on to some COVID treatment protocols as constructed in the following flowchart. As a coach, we only need to concern ourselves with the right branch. However, look to the left side and notice how extensive it is and the time involved. It’s a lot.

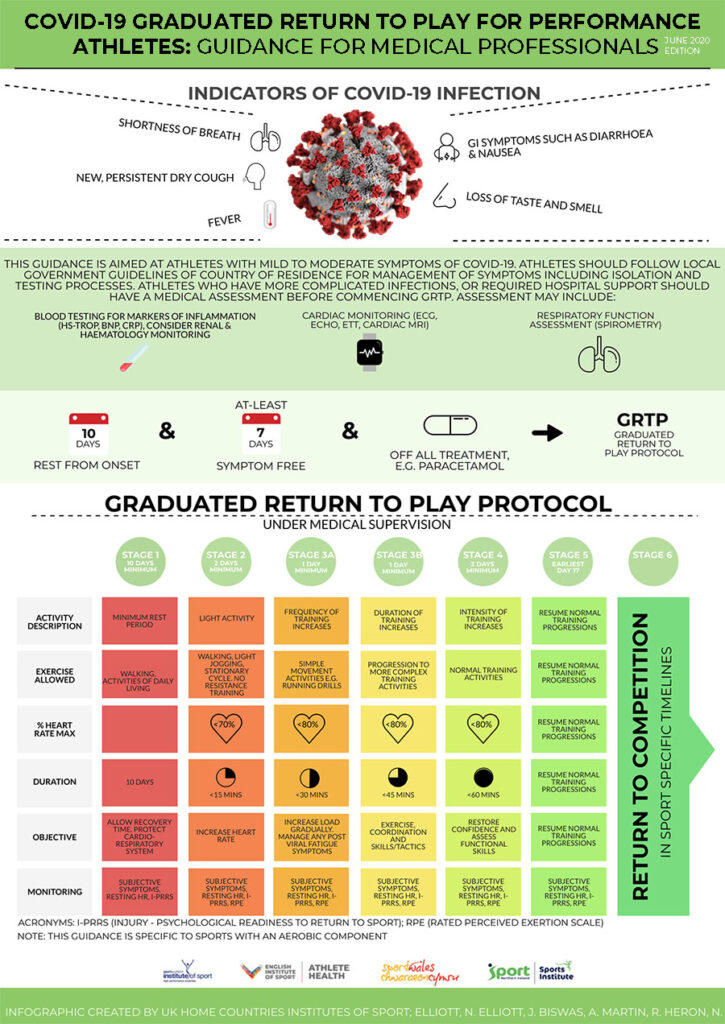

Finally, the bottom right box points to an individualized RTP plan which we can find on the Faculty for Sport and Medicine UK website.

As a coach, you’ll spend most of your time guiding the athlete through the RTP space. There are other protocols, too, and this should be an individualized RTP action plan. One size does not fit all.

Finally, as a coach, it’s essential to support the athlete mentally during this process. Our athletes are accustomed to moving and working and resting. They will struggle to rationalize protocols, especially when they don’t feel “bad.” Keep them aware of why they are resting and remind them that it will end and they will be crushing it soon enough.

Thanks for reading.

References

Daniels CJ, Rajpal S, Greenshields JT, et al. Prevalence of Clinical and Subclinical Myocarditis in Competitive Athletes With Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Results From the Big Ten COVID-19 Cardiac Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(9):1078–1087. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2065

Udelson JE, Rowin EJ, Maron BJ. Return to Play for Athletes After COVID-19 Infection: The Fog Begins to Clear. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(9):997–999. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2079

Kim JH, Levine BD, Phelan D, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 and the Athletic Heart: Emerging Perspectives on Pathology, Risks, and Return to Play. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(2):219–227. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.5890

Martinez MW, Tucker AM, Bloom OJ, et al. Prevalence of Inflammatory Heart Disease Among Professional Athletes With Prior COVID-19 Infection Who Received Systematic Return-to-Play Cardiac Screening. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(7):745–752. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565

Mack CD, Wasserman EB, Perrine CG, et al. Implementation and Evolution of Mitigation Measures, Testing, and Contact Tracing in the National Football League, Aug. 9–Nov. 21, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:130–135.

Klawitter, Paul M.D., Ph.D.*; Cowen, Leslie ATC, MS†; Carhart, Robert M.D.‡ Low Risk of Cardiac Complications in Collegiate Athletes After Asymptomatic or Mild COVID-19 Infection, Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine: July 2022 – Volume 32 – Issue 4 – p 382-386 doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000001043

Risch M, Grossmann K, Aeschbacher S on behalf of the COVID-19 remote early detection (COVID-RED) consortium, et al

Investigation of the use of a sensor bracelet for the presymptomatic detection of changes in physiological parameters related to COVID-19: an interim analysis of a prospective cohort study (COVI-GAPP)

BMJ Open 2022;12:e058274. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058274

Moulson N, Gustus SK, Scirica C, et al

Diagnostic evaluation and cardiopulmonary exercise test findings in young athletes with persistent symptoms following COVID-19

British Journal of Sports Medicine Published Online First: May 18 2022,. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105157

Rosie K. Lindsay, Jason J. Wilson, Mike Trott, et al. (2021) What are the recommendations for returning athletes who have experienced long-term COVID-19 symptoms?, Annals of Medicine, 53:1, 1935-1944, DOI: 10.1080/07853890.2021.1992496