When I was in Kona, I had a disheartening conversation with a female triathlete and her coach about underfueling. “Do you even enjoy what you are doing?” was the question I asked her. A resounding “No” came back. Her coach, Yvonne Spencer with team Fast Chix, was concerned about how little she was eating, sharing that she ate nothing all day, not even before or after a session, except a small dinner and crackers in the evening. The discussion then turned to some questioning about nutrition beliefs, prior nutrition knowledge and education, food preferences, the purpose of training, and medical history.

The athlete’s most notable responses revolved around a belief that if she did not eat, she would lose weight, which would help her perform better. With some further questioning, it was clear that her belief was not hers alone, and that other athletes have similar, inaccurate views on training and nutrition. This article details the perils of undereating and how it can affect the quality of your most important recovery tool — sleep.

What is Undereating?

Low energy availability (LEA) refers to the underlying cause of the female athlete triad and, by extension, Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports Syndrome (RED-S). LEA and underfueling can be used interchangeably.

Defining underfueling (aka, undereating) or LEA via caloric intake equates to the consumption of less than 30 kcal per kilogram of fat-free mass (aka, FFM, or all body components except fat) over a chronic duration for females. The amount for men needs to be more well-defined and may be slightly lower. It can be generalized that a period of up to two weeks at this level of fueling can result in adverse effects on the body, though the exact duration is not definitive, and short-term negative consequences have been linked to fewer days of underfueling.

In the case of the previously mentioned mid-50s Kona triathlete (who I’ll refer to from now on as Athlete X), she was approximately 70 kg with an unknown specific FFM. Her body fat percentage was also unknown and estimated to be around 30%. Based on her information, her daily caloric intake was around 700-900 kcal, which was far too low and had been occurring for far too long (over three months).

The key part of the LEA equation is that intake is less than expenditure. In other words, there must be an imbalance between how much an athlete eats and the energy that they expend via exercise, non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), and dietary-induced thermogenesis (DIT). Having a higher expenditure than intake will result in a reduction in body mass — including fat, muscle, water, or bone mass — over time. It is important to note that underfueling can be intentional (i.e., to restrict calories to lose weight purposefully) or unintentional (i.e., avoiding a specific food group like carbohydrates that results in inadvertent caloric restriction).

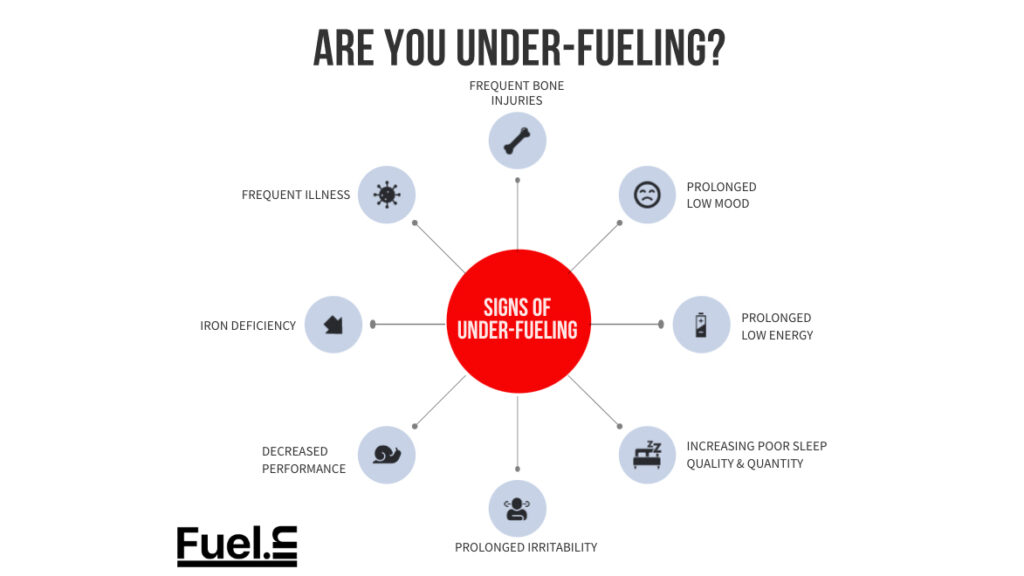

It should be noted that there are limitations to estimating energy intake and expenditure in the real world, which means it is essential to recognise the signs and symptoms associated with underfueling. This is the case even if fueling guidance is being provided by a professional, as their calculations may be off. LEA can affect multiple aspects of an athlete’s life, but the focus of this article is its effects on sleep. As you will read, this negatively affected Athlete X’s health — particularly her sleep.

Symptoms of Undereating: Poor Sleep

As part of my discussion with Athlete X, I asked if she had had any sleep disturbances. She reported that she had been suffering from poor sleep quality and duration for the past six months. Athlete X also reported night sweats and difficulty falling asleep. This coincided with her training and current dietary strategy.

Signs and symptoms of undereating include:

- Poor sleep quality

- Reduced deep or short-wave sleep (SWS) duration and percentage, which can be identified with a wearable device like Oura or Whoop

- Difficult falling asleep

- Difficulty staying asleep

- Night sweats

It’s important to note that these sleep disturbances can be caused by other mechanisms and are not necessarily diagnostic of low energy availability or underfueling. If they are present, you should discuss them with a sports nutritionist, dietician, or your doctor to exclude other reasons for sleep disturbances, such as sleep hygiene, menopause, and other disease processes.

Interestingly, Athlete X reported that she had discussed her sleep troubles with her doctor and that it was explained these were signs and symptoms of menopause. Whilst this may be the case, with a little deeper questioning, it should have been evident that Athlete X was underfueling and that it could be contributing to her sleep issues.

This is important to raise with any medical personnel you are seeing. Firstly, explain that you are training for a sport or race that a tiny percentage of the world attempt. Therefore, consideration must be given to what is “normal”, as this may not be normal for you. Secondly, be open with your story and assist the health care professional with as much information as possible. In Athlete X’s case, disclosing her nutritional intake pattern and training volume should have been enough to raise some alarms in her doctor’s mind. In defense of Athlete X and her doctor, when I questioned her about the link between fueling and sleep, she did not know the relationship and thus may not have been able to disclose this information in a meaningful way.

Can You Improve Your Sleep by Eating More?

This may seem obvious, but in reality, many factors — including psychology, behavioural patterns, environment, cultural beliefs, training load, and an athlete’s purpose or motivation — convolute the answer.

For athletes identifying with some of the information in this article, the first place to start is an acceptance that under-fueling might be present and that something must be done. Beyond this, the recommendation would be to seek the professional guidance of a nutrition expert. This should ideally be a consultation before any sort of program is developed. A thorough understanding of training load (volume and intensity) coupled with athlete beliefs, knowledge, skills, and habits is paramount to success. In the case of Athlete X, her underfueling was intentional, yet she did not understand its consequences.

There are other aspects to consider when addressing poor sleep and how it can be improved. Increasing your intake of fruit and vegetables has been researched and shown to improve sleep duration and quality, which could also be a strategy for Athlete X to consume more calories.

Three practical strategies to improve sleep through nutrition include:

- Eating 60-100 g of high glycemic carbohydrates for dinner at least 60 minutes before bed. This could include potato, sweet potato, bread, rice, grains, and fruit.

- Combining a quality source of at least 30-40 g of protein (preferably animal protein if dietary preference allows) with those carbohydrate ingredients (e.g., fish, red meat, dairy, pulses, and/or grains).

- Ensuring your urine is clear and non-smelly before bed. If not, aim to consume water throughout the day. Approximately two to three litres is a good starting point, but this will vary depending on training and environmental conditions.

After extensive discussion and explanation, Athlete X had clear advice on what to do next. The first was eating a bowl of oatmeal with banana and toast the following morning before her two-hour ride. The second was consuming an almond-butter sandwich cut into triangles during the ride and drinking water as thirst demanded. She felt a lot better during and after that session. It was a starting point with a lot more work required.

References

Areta, J.L. et al. (2020, October 23). Low energy availability: history, definition and evidence of its endocrine, metabolic and physiological effects in prospective studies in females and males. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33095376/

Mountjoy, M. et al. (2018, May 17). IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Retrieved from https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/52/11/687

Stellingwerff, T. et al. (2021, June 28). Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34181189/