Every runner knows pacing is critical. It can be the difference between a PR and a DNF. In On Pace, acclaimed running coach and author Matt Fitzgerald reveals how conventional training and device overdependence keep runners from accessing the full power of pacing.

With a mix of fascinating science and compelling stories from every corner of the sport, Fitzgerald shows that pacing is the art of finding your limit — running at a pace to finish the workout or cross the finish line completely out of gas. This quintessential running skill unlocks hidden potential and transforms your experience of the sport, enabling runners of all experience and ability levels to “run free.”

Chapter 5, “The Mind of a Pacing Master”, of On Pace is made available to you below. You can purchase your own copy of Matt Fitzgerald’s book On Pace here. Additionally, you can access an extensive selection of 80/20 Endurance running training plans from the TrainingPeaks training plan store.

Excerpt From Matt Fitzgerald’s Book On Pace : Chapter 5, “The Mind of a Pacing Master”

The best pacer I’ve ever run with is Ben Bruce, a now-retired professional runner and former member of the Flagstaff-based HOKA Northern Arizona Elite team. When I joined the group as an honorary member in the summer of 2017, I was far too slow to do anything other than easy runs with Ben and his fellow elites, but as luck would have it, Ben was injured that summer, and he was kind enough to pace me through a few key sessions while rehabbing what, at the time, he thought was a hip flexor strain but turned out to be a pelvic stress fracture.

The first of these sessions was a long progression run on Lake Mary Road, a hallowed proving ground for Flagstaff-based marathoners. As Ben ran alongside me, I was struck not only by his ability to nail the mile splits I gave him but also by how much thought he put into the process. Aware that I would be doing a lot more running, most of it alone, on the same highway in the coming weeks, Ben shared a litany of tips on how to stay on pace, noting tricky false flats, exposed stretches where headwinds were common, sharp descents that offered opportunities to bank time, and so forth.

In light of this experience, I wasn’t the least bit surprised when Ben later transitioned into a coaching role with NAZ Elite that involved extensive pacing work. His pièce de résistance was a job leading Keira D’Amato to the seventh-fastest marathon time ever recorded by an American woman (2:22:56) at the 2020 Marathon Project in Chandler, Arizona. It was, I’ll grant, a relatively straightforward pacing task, given the course’s pancake-flat, multiloop layout, which facilitated a steady rhythm, but Ben made it look much easier than it was, shepherding Keira through 5 km splits of 17:02, 16:58, 17:02, 16:59, 16:55, 16:59, 16:55, and 16:56 before Keira dropped the hammer over the last 2.2 km as Ben peeled off.

If you’re skeptical of the notion that some runners have an innate knack for pacing, good luck explaining Ben Bruce’s mastery. Raised in San Diego, he got a relatively late start as a running specialist, competing in his first-ever track race as a college freshman after earning varsity letters in golf, soccer, and cross country during his high school years. Yet despite having less experience than his fellow Cal Poly Mustangs, Ben was by far the most reliable pacer on the team, in recognition of which the senior captains awarded him the pressure-laden honor of leading the crucial first repetition in workouts.

In Chapter 8, we’ll talk about macro pacing, or pacing on a long time scale. Many if not most runners who are good at pacing individual runs are equally good at pacing their overall running career. Ben proved to be great at both, pacing himself to a professional running career that lasted nearly two decades, earning the distinction of being the only runner ever to qualify for and compete in sixteen straight USATF Outdoor Championships. And though he might not like my mentioning it, Ben is also the only runner ever to have finished tenth, ninth, eighth, seventh, sixth, fifth, fourth, third, and second—but never first—in national championship races.

The secret to Ben’s pacing mastery is no secret. Like all pacing masters, Ben is a virtuosic self-regulator on the roads, trails, and track, endowed with all three of the key mental traits that pacing skill depends on. Body awareness? Check. Ben showed exceptional interoceptive sensitivity in leading his wife, Stephanie Bruce, through a bull’s-eye 5:34 opening mile at the 2019 Chicago Marathon, where GPS data are famously unreliable, setting her up perfectly to record a personal-best marathon time of 2:27:47, averaging 5:38 per mile for the full distance. Judgment? Also check. Ben’s remarkable judgment was expressed in a patient, methodical, even-keeled approach to training and development that enabled him to just keep getting better and better year after year. “I have always had a consistent mindset,” he said in a 2012 interview for RunCoach.com. “Chipping away at times over the years has been the way that I have gotten to where I am as a runner today. . . . Not any one workout will make you a superstar, but a bunch of solid ones will make you super strong and ready to race.” Toughness? Checkmate! I saw Ben’s toughness firsthand in the summer of 2017, when he ran through the pain of an as-yet undiagnosed pelvic stress fracture that would have immobilized most runners.

As a coach, Ben shares my belief that you don’t have to be a natural-born pacing master like him to become one. The preceding chapters served to define the mission: To master the skill of pacing, one must cultivate the capacity to self-regulate both during runs (exercising behavioral control in relation to the goal of finding one’s limit) and between runs (exercising behavioral control in relation to the goal of learning to pace better). Cultivating the capacity to self-regulate, in turn, requires the development of body awareness, judgment, and toughness. The goal of this chapter is to offer practical instruction on how to do this. None of the methods you’ll learn here qualifies as a quick fix, much less a “hack.” The road to pacing mastery is long, but there’s a prize at the end of it—the sublime joy of running free, which is to say, of knowing what you can do and then going out and doing it, every time.

Learning Body Awareness

A distinction can be made between general body awareness and task-specific body awareness. General body awareness, or interoceptive sensitivity, is the broad capacity to feel one’s body, which is measured through tests such as counting one’s heartbeats by feel. Specific body awareness is the trained feel for certain body parts or movements that comes through skill development. The task-specific body awareness that, for example, a tightrope walker develops through training for his vocation is different from the body awareness that a runner develops through training for her sport. Whereas the tightrope walker learns a refined sense of balance, the runner hones a precise perception of effort, as well as other kinds of interoceptive sensitivity, including the kind Kenenisa Bekele used to keep his hamstring from shredding while fighting to remain in contention for victory in the 2019 Berlin Marathon.

As a runner, you’re not interested in developing forms of body awareness that have little relevance to your sport. The time and energy you invest in improving your body awareness need to go toward measures that offer the greatest benefit to your running. Three of my favorites are body scanning, condition assessment, and time-limit estimation.

Body Scanning

Research has demonstrated that meditation and other forms of mindfulness (a state of receptive attention to the present moment) improve body awareness by modulating the insula, a brain region involved in interoception. Body scanning is a mindfulness practice that targets body awareness directly, and it can be done both during running and at rest.

Running Body Scan

To scan your body while running, focus your attention on one small piece of your overall experience at a time, pausing long enough to notice everything there is to notice before moving on to the next piece. Your breathing is a good place to start. Don’t try to control or change it; just notice it. Take some time to attend to your perception of effort. Try to pick up its nuances. Words such as “hard” and “easy” don’t even begin to capture all that’s going on with effort perception at any given moment. For example, the sort of hard effort you might experience when running slowly in a state of extreme fatigue is very different from the sort you might experience during the third lap of a one-mile track race.

Other aspects of the running experience you can focus on include soreness and other forms of discomfort in your musculoskeletal system, the rhythm of your arm and leg movements, specific parts of your body (even your toes!), tension in your face and shoulders, your perception of speed and movement through space, and the various interfaces between your body and the environment: contact between your feet and the ground, gravitational resistance, and the feeling of air brushing against your skin.

Runners are always aware of their body when running, of course, but conducting a formal body scan while running is as different from this default awareness as meditation is from daydreaming. The goal is not to scan your body continuously throughout every run—that would drive you nuts. Focusing too much on internal perceptions is actually harmful to performance, for reasons I will explain when we explore race pacing in Chapter 7. Just scan your body for a few minutes at a time when it crosses your mind to do so. Over time, you will develop a better sense of how to interpret and use what you’re feeling to inform your pacing decisions.

Body Scan Meditation

If you practice meditation, adding body scan meditations to your routine can be a nice complement to running body scans. These can be done anytime—before a run, after a run, or whenever you normally meditate. Sit comfortably in a quiet environment and allow your attention to roam from one focal point to the next. Start by attending to the overall position of your body, then concentrate on where you are in space and how you’re feeling generally (e.g., warm, calm, thirsty). Next, seek out areas of tension in your body, just noticing the feeling rather than trying to get rid of it, and then shift to your breathing. Now move your attention slowly from the top of your head to your face, neck, shoulders, chest and heart, arms, torso, stomach, bottom, upper legs, knees, lower legs, ankles, feet, and toes. Finally, do the whole thing in reverse, returning step by step to the overall position of your body.

If you’re so inclined, include a heart rate estimation test in the occasional body scan meditation. To do this, you will need to wear a heart rate monitor with a timer. Take a few moments to focus your attention on the feeling of your heart muscle’s contractions. Start the timer and begin to count the contractions. Continue for one minute, then stop the time and check your total against the current heart rate reading on your watch. See if you can improve your accuracy with repeated practice. You can be sure that any improvement you do achieve will translate into better interoceptive sensitivity when running, hence better pacing ability.

Condition Assessment

When I last spoke to Ben Bruce, I asked him how fast he thought he could run a 10K race at his present fitness level. Without hesitation, he answered, “Twenty nine something.” Mind you, Ben wasn’t training for a 10K at the time. His recent running had lacked any real structure, consisting of a mix of pacing work for NAZ Elite members and easy runs done on a catch-as-catch-can basis. Yet he seemed quite confident in his prediction, and I have no doubt that his answer would have proved accurate had he given in to my arm-twisting and actually raced a 10K the next day.

Where does this kind of self-knowledge come from? I believe it comes largely from condition assessment, a practice whereby runners use each and every run they do to assess their present fitness level. This is something all runners—including those who struggle with pacing—do when circumstances demand it, such as when a runner who is training for a 10K race does a set of intervals targeting 10K race pace. But pacing masters like Ben conduct a form of condition assessment in all their runs, and the sheer volume of information generated through this habit is what makes the difference. Put another way, what makes a pacing master a pacing master is that he gets a feel for how fast he could race a 10K not just from a 10K-pace workout performed on relatively fresh legs but also from a random, short recovery run performed on tired legs the day after a hard workout.

To succeed in gleaning information about your fitness level from runs of various kinds you must properly contextualize what you’re feeling. Let’s return to the example of a run that comes the day after a hard workout. It’s likely, of course, that you will feel tired and run slow in any such run. But it’s possible that you will feel somewhat less tired and go somewhat faster than you have in recent runs performed in similar circumstances, and if you do, you may conclude from this information that your training is going well and you’re getting fitter.

When conducting condition assessments, it’s helpful to place today’s run in an even broader context, comparing how you’re feeling and performing—all things considered—against how you’ve felt and performed in similar circumstances in previous training cycles. Again, one such comparison won’t tell you much, but routine comparisons of this type will aid you in setting goals and performance expectations for upcoming races.

Just be careful not to allow your condition assessments to become a source of anxiety. Approached with the wrong mindset, this practice could easily cause you to train in a state of perpetual worry about whether you are on track toward a goal, sort of like how weighing yourself too often or obsessively checking your stock portfolio can make you freak out needlessly. It’s a matter of keeping perspective. If you complete a long run on a hot day after a poor night’s sleep with thirteen weeks remaining before a marathon, when you’re still relatively far from peak fitness, don’t interpret the misery you experience in the late miles as proof that you’re doomed to fail in your marathon. Conduct your condition assessments with a mindset of neutral curiosity. Account for everything—the heat, the lack of sleep, your modest fitness level, the thirteen weeks you’ve got to get fully race-ready—in assessing your condition, and maintain the same neutral mindset in all of your condition assessments. Don’t interpret your runs as if your race is tomorrow unless, in fact, your race is tomorrow.

Time-Limit Estimation

Another simple exercise that you can perform routinely in the course of your normal training is time-limit estimation. This practice entails asking yourself how long you think you could sustain your present pace or, alternatively, selecting a pace you feel you could sustain for a specific amount of time. Like condition assessments, time-limit estimation, when used intentionally as a tool for learning body awareness, is nothing more than a broadened application of something all runners do automatically in races and time trials, during which every runner estimates, consciously or unconsciously, how long they can keep up their current pace.

Experience supplies runners with a general idea of how long it’s going to take to complete a run, and at each point along the way we ask ourselves, explicitly or implicitly, Can I hold this pace the rest of the way? Experiments like the University of Lille study mentioned in Chapter 3 have shown that higher performing endurance athletes are better at estimating how long they can sustain a given output, and that’s why conscious time-limit estimation is a worthwhile pacing exercise.

Like condition assessments (and body scanning), this exercise is one you can sprinkle into your training in a playful way, employing it whenever the mood strikes you. Again, we’re all accustomed to estimating our time limit in races and time trials, but what I’m advocating is conscious use of the same faculty in other situations—easy runs, long runs, tempo runs, whenever. It’s just another way of making you more mindful of what your body’s telling you about its abilities and limits.

Time-limit estimation is also useful as a way to regulate intensity in runs. Such estimates may either replace or supplement objective metrics used for the same purpose, such as pace. For example, most runners, regardless of fitness or ability, are able to sustain their VO2max pace (or the slowest pace at which they achieve their maximal rate of oxygen consumption) for about six minutes. Therefore, you can target VO2max intensity in an interval workout by selecting a pace you feel you could sustain for six minutes.

Even when you do choose to use an objective measure as your primary intensity metric in a given run, estimated time limits have a role to play, helping you find the appropriate effort quickly, before your device has a chance to catch up to a shift in speed, and also helping you adjust your pace as you go based on factors like elevation change and fatigue. I’ll have more to say on this subject in the next chapter.

Cultivating Judgment

Similar to body awareness, judgment operates on two levels, general and task-specific. At both levels, judgment expresses itself through decisions. People who have general good judgment make good decisions in most areas of their lives. But we all know people who make good decisions within a special area of expertise while showing poor judgment in other areas. Every great athlete makes consistently good decisions within their sport, but not every great athlete also makes good decisions with money, in relationships, and elsewhere. To master the skill of pacing, you will need to cultivate better pacing judgment, and the way to do it is reasonably straightforward.

Research has shown that teaching athletes sport-specific decision-making skills improves their judgment on the field of play. A 2013 study conducted by Spanish researchers and published in PLOS One explored the effect of decision making skills training in junior tennis players. Eleven players were separated into two groups, both of which played eighteen full matches that were videotaped. The first four matches were used to establish a baseline (so to speak) of decision-making competence.

After each of the next ten matches, the five members of the decision making skills training group sat down to review tape of selected points with a coach, who asked the players to explain and critically evaluate their decisions in a guided manner. The six members of the control group received no such training. In the last four matches, decision-making competence was reassessed. On average, players in the decision-making skills training group were found to have improved their decision-making scores by 10 percent, whereas the players in the control group showed no improvement.

In my one-on-one work with runners, I’ve found that a similarly intentional approach to improving decision-making can improve pacing judgment. The tool I rely on most for this purpose is decision tracking, which is similar to the method used in the study just described. The key difference is that there’s no video involved. It’s just a mental performance review that can be done in the context of your training log. After each workout or run involving important pacing decisions, devote some space in your training log to assessing your decisions in the five areas that I first enumerated in Chapter 4: planning, emotional self-regulation, self-talk, tactical adjustments, and attentional focus.

Planning

Pacing decisions are made before a run even begins. This goes for both races and training runs, but for now let’s focus on training. Among the decisions you’ll need to put some thought into before training runs are where to run, what your pace and time targets will be, and who to run with. There’s no need to fuss over such decisions ahead of less important workouts, but when there’s a lot riding on a particular run, you’ll want to set yourself up for success in every way possible (for example, find someone like Ben Bruce to run with you!).

The most common mistake runners make in setting workout pace targets is basing their decisions on their aspirations rather than on a realistic assessment of their current fitness. Aspirational workout goals inevitably lead to overreaching and frustration. Remember to always train as the athlete you are today, not as the athlete you hope to be on race day. Ensuring that your training consistently meets you where you are is precisely how you become the athlete you hope to be down the road.

Be sure to give yourself credit for good decisions as readily as you call yourself out for bad decisions. The researchers who conducted the tennis experiment I just described made a point (so to speak) of having subjects review as many situations in which they made the right decision as those in which they choose the wrong move. So, for example, if procrastination left you with no option other than to run in the heat of the afternoon, thereby putting you out of reach a target pace that would have been manageable in the cool of the morning if you’d only gotten your lazy ass out of bed, take yourself to task. And if you nail a workout after turning down an invitation from a friend who always half-steps you and drags you out of your proper rhythm, pat yourself on the back. In either case, the process will improve future decisions.

Emotional Self-Regulation

Affect, or emotion, plays an important and underappreciated role in pacing. Remember, pacing is the art of finding your limit, and negative thoughts and feelings make it harder—impossible, really—to reach your true limit. This was shown in a fascinating study conducted by researchers at the University of Worcester and published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. Fourteen runners completed 10K performance tests on two occasions—once alone and once in a group. On average, they ran 58 seconds faster in the group test, yet their pacing patterns were the same in both. The difference was that the runners experienced higher levels of positive affect in the group 10K. In other words, they ran closer to their limit with others because they were enjoying themselves more.

You, too, will perform better if you keep your emotions within the neutral to-positive range and out of the negative zone in races and workouts. One way to do this is with positive self-talk, which is the subject of the next section. But before you can engage in positive self-talk, you sometimes need to stop negative thoughts. This entails mentally “catching” negative thoughts quickly and overriding them. For example, you might start thinking, “I hate how I’m feeling right now,” during a workout, then realize you’re thinking this and consciously put a stop to it. Doing so won’t change the fact that you’re suffering, but it will keep your mind from exacerbating the situation and dragging down your performance.

Acceptance is another technique that is proven to mitigate negative thoughts and feelings during exercise and to thereby enhance performance. This entails making peace, or being okay, with your discomfort. You’re not trying to persuade yourself that you’re not really uncomfortable—that doesn’t work. Rather, you’re accepting your discomfort as a necessary part of the task you’re performing. You can’t control how you feel when you’re running, but you can control how you feel about how you feel, and acceptance is the most performance enhancing feeling you can possibly have about exertional discomfort. Research has shown that consciously accepting discomfort increases endurance performance. It’s mainly a matter of embracing the fact that discomfort is inextricably linked to the things that make finding your limit worthwhile for you. As the Nepalese elite ultrarunner (and former adolescent guerilla fighter) Mira Rai said in an interview for the Mindful Running podcast, “Running makes me happy. When you’re happy doing whatever you do, pain becomes secondary.”

Acceptance works best when it begins before running. You accept that the run is going to hurt and then, when it does, you accept that it does, which is always easier to do when the discomfort was anticipated. In a 2021 interview for Athletics Weekly, Norwegian elite middle-distance runner Jakob Ingebrigtsen described how he uses this anticipatory acceptance technique in racing: “I usually get really nervous, not only because of my expectations but it’s also about the pain. . . . I don’t enjoy being in pain. . . . If you are really well prepared and you do what you need to do going into that race, it’s going to end up pretty good and you’re not going to feel that much pain after all. But I know, going into my next race, I get really nervous [again] because of the pain. But I think that’s my way of preparing myself physically and mentally for each race—to be nervous of the pain that’s coming but also to be awake and focused on the task so I can run as fast as possible.”

It’s worth mentioning that Ingebrigtsen was only twenty years old when he spoke these words. You can be certain he wouldn’t have accomplished all he had at such a young age (having already set numerous national and European records and won European and World Championships medals, he became the second-youngest athlete ever to win the Olympic men’s 1500m event at the 2021 Summer Games in Tokyo) without such a strong capacity for emotional self regulation. Take a cue from Jakob Ingebrigtsen and, as part of your post-run decision tracking, rate how well you regulate your emotions before and during it. Give yourself full credit for successful thought-stopping and acceptance, and admit where you fell short.

Self-Talk

I’ve always thought of “self-talk” as being a little corny. It brings to mind children’s stories like The Little Engine That Could or Al Franken’s Stuart Smalley sketch on Saturday Night Live—“I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me!” Corny or not, though, self-talk impacts pacing, for better or worse. The kind of encouragement these fictional characters gave themselves is proven to enhance endurance performance. A study led by Samuele Marcora and published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise in 2014 reported that training in positive self-talk improved performance in a high-intensity ride to exhaustion by 17 percent.

This type of “note to self” works best if it has personal significance or addresses a specific need. One-size-fits-all mantras like “I think I can” are better than nothing, but you’ll get more mileage out of phrases that speak to your individual weaknesses and immediate challenges. For example, if you are prone to self-doubt, and you find such feelings bubbling up at a tough moment in a race or workout, you might choose to think, “Nothing to prove,” to remind yourself that you are worthy, win or lose, and all that matters is trying your best. And if you find yourself beginning to overheat during a race and are concerned that dialing back your effort in response to this feeling will put your podium ambitions in jeopardy, you might choose to think, “It’s hot for everyone, not just me.”

Self-talk can also be used in more tactical ways to assist pacing. Two-time Olympian Ajeé Wilson of the United States liked to mentally divide her 800-meter races into two parts, the first 300 meters, which were all about positioning herself for the last 500 meters, and those painful last 500 meters, at the start of which she mentally recited the same script every time: You’re okay. You’re comfortable. You’re fine.

Does every great half-miler use this same script? In other words, is Wilson’s self-talk ritual necessary to optimize pacing in an 800-meter race? It is not. But tactical self-reminders of some kind, which can vary from runner to runner and from event to event, are required to find your limit, and they are equally helpful in workouts run below the limit. Over time, decision tracking can help you discover the particular internal messages that work best for you, just like Ajeé Wilson.

Tactical Adjustments

When Ben Bruce set his half-marathon personal best in Tempe, Arizona, in 2016, he faced a critical decision around 5 miles, where the lead pack he’d been running in broke apart as top contenders Scott Bauhs and Karim El Mabchour accelerated to a pace that felt a bit too quick for Ben. There were two options: go with the pacesetters anyway and risk hitting the wall, or avoid this risk by holding back and giving up on any chance of winning. He opted to roll the dice, and at 10 miles he found himself not only still in contention but feeling surprisingly strong, so he continued to press, chasing Bauhs all the way to the finish line for second place.

This is one example of the sort of tactical pacing decision runners are required to make all the time in workouts and, especially, in races. Over the course of a longer event like a half marathon, dozens of such decisions are made, and they range from whether to slow down and tuck behind a taller athlete while running into a headwind to whether to disregard a mile split that’s so far off expectations as to suggest the possibility of measurement error.

It is beyond the scope of this book to offer comprehensive guidance on how to handle every conceivable type of tactical pacing decision you might encounter. Nor should you want such guidance. The goal is to become confident in your own ability to handle tactical decisions, not to have these decisions made for you!

In all seriousness, the tactical element of pacing is one of those things that’s more learnable than teachable. By this I mean that intentional practice will take you a lot further than an encyclopedia of if-then instructions from me or any coach. For this reason, decision tracking is especially valuable in its application to tactical pacing decisions. It doesn’t matter how bad your tactical decision making is today. By reviewing and grading your pacing decisions routinely, you will become increasingly confident in the calls you make in the heat of the moment. But what if you lack the confidence to even distinguish good pacing decisions from bad ones? In this case, consider working with a coach to build a base of knowledge for your confidence to rest on.

Attentional Focus

The relevance of attentional focus to pacing is obvious. No runner has ever paced a race or hard workout optimally by daydreaming their way through it—at least not that I’m aware of.

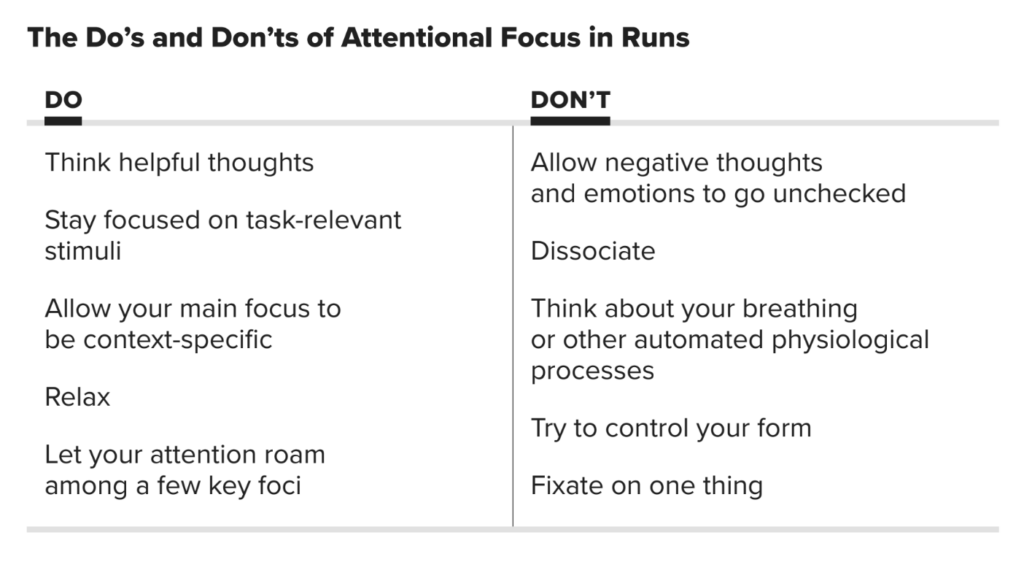

There’s an almost infinite variety of things you can focus your attention on when running, but all fall within a handful of broad categories. At the most general level, your attention can be focused either externally or internally. When focused externally, your attention can be directed toward task-relevant stimuli, such as a big puddle on the trail ahead that you’ll want to avoid splashing through, or non-task-relevant stimuli, such as a squirrel scampering across a tree branch above you.

When focused inward, your attention may be directed toward thoughts, emotions, body sensations, physiological processes including breathing, and actions such as your step rate. These too may be either task-relevant (an example being assessing your thirst intensity) or non-task-relevant (like wondering how the Green Bay Packers are doing in their big showdown against the Chicago Bears). An internal attentional focus may also be metacognitive, meaning you’re thinking about what you’re thinking or feeling, an example of which is assessing whether your current perceived effort level is appropriate for the moment.

All of these examples of attentional focus may also be proactive or reactive in nature. Proactive attention entails choosing its object, as when you glance at your device to check the elapsed time, while reactive attention entails responding to a stimulus, often involuntarily, as when you hear your name shouted and glance to the right, where you see your cousin Sam cheering you on.

Research has shown that certain uses of attentional focus tend to aid performance while others tend to hinder it. Broadly speaking, non-task-relevant foci like thinking about what you’re going to eat after the race are unhelpful. Sometimes you’ll hear disappointed elite runners chastise themselves in post race interviews for “losing focus.” Seldom are such lapses as egregious as making mental shopping lists during competition, but virtually any distraction from the task at hand will negatively affect pacing and performance.

The mental trick known as chunking can be helpful in maintaining focus during longer events, where staying focused is especially challenging. Sport psychologist Noel Brick, whose research concentrates on how elite endurance athletes use their minds during training and competition, defines this trick as “mentally breaking down the distance to smaller segments.” Thirty kilometers into a 50K ultramarathon, thinking about the finish line may be overwhelming, but thinking about reaching the next aid station is far less so.

The one circumstance in which dissociation, or intentionally not focusing on the task at hand, can be beneficial is when a runner’s discomfort level verges on intolerable. There’s a great example of helpful dissociation in novelist Haruki Murakami’s memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. While competing in his first ultramarathon, Murakami hit a rough patch during which he tried every psychological trick he could think of to keep running despite the overpowering desire he felt to stop. As a last-ditch measure, he tried telling himself, “I’m not a human. I’m a piece of machinery. I don’t need to feel a thing. I just forge on ahead.” To his amazement, this self-admittedly unhinged internal pep talk worked. Murakami did not literally turn into a machine, of course, nor did he actually cease to feel a thing, but somehow the very repetition of this thought enabled him to find a certain peace within his suffering and catch a second wind. “My muscles silently accepted this exhaustion now as a historical inevitability, an ineluctable outcome of the revolution,” he writes. “I had been transformed into a being on autopilot, whose sole purpose was to rhythmically swing his arms back and forth, move his legs forward one step at a time.” In this trance-like state, Murakami found himself easily passing the scores of runners who had passed him during his earlier rough patch. “It’s weird, but at the end I hardly knew who I was or what I was doing,” he reflects. “By then running had entered the realm of the metaphysical. First there came the action of running, and accompanying it there was this entity known as me. I run; therefore I am.”

As I say, though, except in emergencies, dissociation tends to harm pacing and performance, as does thinking about or trying to control physiological processes such as breathing. Focusing on your movements can go either way. As a general rule, doing so is helpful when your attention is directed toward the interface between your body and the environment or on staying relaxed, whereas it’s unhelpful when it’s used to try to run “correctly” in some way. In a study that Noel Brick did on mental processes in elite runners during training and racing, self-reminders to relax were among the most commonly cited meta cognitive strategies.

Different situations demand different attentional foci, and studies involving elite endurance athletes indicate that the highest performers are adept at selecting the right focus for each moment. If you think about it, this makes sense. In the early part of a marathon, for example, when you’re feeling energized and excited, it might be best to pay extra attention to the current pace reading on your device as a way to prevent overzealous pacing, whereas in the late part of a marathon it’s better to ignore your device completely in favor of feeling your way to the limit and urging yourself forward with positive self-talk.

At all times, though, your attention should roam. Whether you’re 2,000 meters into a 10,000-meter track race or working your way through hill repetition number six in a set of ten, you’ll get the best outcome if you shift your attention from one object to another within a limited set of perceptions, thoughts, and emotions. Pacing masters develop a natural rhythm in their attention cycling, a sort of attentional loop that moves from effort assessment to context-specific self-talk to pace checking and back to effort assessment (for example), with allowances for reacting to salient stimuli and changing the contents of the loop as the run unfolds.

The opposite of such tactical attentional roaming is fixation. Allowing your mind to fixate on something is almost always harmful to pacing and performance. Most often this occurs when a runner is experiencing a high level of discomfort, which then dominates their attention in the way that extreme pain does, but there are also many examples of runners fixating on less threatening elements of their experience such as negative thoughts (“I’m behind my goal pace”) or emotions (such as disappointment) or even device data. At a press conference I attended after the 2010 Boston Marathon, a reporter asked Ryan Hall why he’d looked at his watch so frequently during the first mile of the race, which Hall had completed in 4:36. Hall explained that he had done it in an effort to keep himself in check, having run the same mile in an absurdly quick 4:29 in his Boston debut two years earlier. Not quite satisfied with this answer, the reporter informed Hall that he’d glanced at his watch no fewer than seventeen times in that first mile.

“I guess that is a bit excessive,” Hall laughed.

So, hey, even the pros do it. But just as Ryan Hall (who, by the way, finished third that day in 2:08:40) admitted to fixating too much on his watch in the opening mile of the 2010 Boston Marathon, you, too, should confess your errors in attentional focus in your training log, while also noting what you did right. The following table presents the basic do’s and don’ts of attentional focus during running, which you can use in making these assessments. Note that they apply only in races and workouts where your goal is to find or approach your limit. Different rules apply in easy runs, which we will talk about in the next chapter.

Building Toughness

I am living proof that a runner doesn’t have to be born tough to become tough. As a high school runner, my aversion to the pain of racing was so extreme that I committed unforgivable acts of cowardice such as faking injuries to escape it. When I got back into competitive running in my late twenties—having quit years before to escape the pain of racing once and for all—I was determined to exorcize the demons that sabotaged the first act of my running life, which meant embracing the suffering I’d previously shied away from. In this second act of my running life, the pain of racing was no longer just a vitiating part of the experience but the very point of it. I wanted not just to run well but to see myself as a tough person, and to this end I measured myself less by how quickly I ran than by how close I got to my absolute limit in the effort to run quickly.

Success didn’t come overnight, but it did come. I will never forget the moment when, minutes before the start of Ironman Santa Rosa in 2019, I realized that I couldn’t wait for the ten hours of strain and pain that lay ahead, and that I was as calm as I would have been before an easy 6-mile run on a random Tuesday. This state of mind could not have been more different from my state of mind before my first Ironman in 2002, when my last words (spoken to my brother Sean in response to the question, “How are you feeling?”) before walking to the start line were, “I’m shitting my pants.” It was a difference that made a difference, as the older but tougher version of me completed the Ironman distance 25 minutes faster than the younger but weaker version of me.

The keys to my transformation were meaning and practice. Becoming mentally tough was personally meaningful to me, so I worked hard at it. But meaning alone didn’t suffice to get the job done. I needed to practice at being tough, again and again, for many years, gaining a bit of ground each time, like an actor overcoming stage fright not through hypnosis or some other instantaneous cure but by getting back on stage night after night.

According to science, mental toughness is 50 percent genetic, which means it is also 50 percent nongenetic, and for those of us who weren’t born tough it is the desire to be tough that makes us tough. As the 18th-century English poet Horace Smith put it, “Courage is the fear of being thought a coward.” Again, Steve Prefontaine’s frequent use of the word “guts” comes to mind. In one famous instance, Pre said, “A lot of people run a race to see who is the fastest. I run to see who has the most guts.” Regardless of how many or how few toughness genes you were blessed with, only by consciously prizing toughness— perhaps even making it the very point of your racing at certain times—will you fully realize your potential for toughness.

Again, though, it takes practice. One of the most consistent research findings in this area is that, for all of us, mental toughness requires repeated exposure to challenging and stressful situations that test our toughness. It was on the basis of this finding that exercise scientist Lee Crust and psychologist Peter Clough wrote in a 2011 article appearing in the Journal of Sport Psychology in Action that “to develop mental toughness, young athletes must be gradually exposed to, rather than shielded from, demanding situations in training and competition in order to learn how to cope.” I would only add that the same holds true for adult athletes.

Other experts in the field of mental toughness have developed systematic methods for cultivating this trait in athletes. The two methods that I found especially helpful in building my own mental fitness and have applied successfully with athletes I coach are accountability cues and limit testers.

Accountability Cues

Codes, pledges, credos, mantras, and related tools can be used to hold oneself accountable to a certain standard of behavior. Through them, athletes and others transform vague intentions into explicit rules, and therein lies their power. In stressful situations, like when you’re struggling in a race and beginning to doubt your ability to achieve your goal, it can be difficult to spontaneously come up with a thought or a snippet of self-talk that delivers just the right message to enable you to hang in there. Different from positive self-talk, accountability cues are more corrective in nature, and they obviate the problem of coming up with a way to stay on track by allowing you to fall back on prepared words that represent the athlete you want to be when the going gets tough.

It’s no accident that many elite runners and other top athletes who are celebrated for their toughness have relied on accountability cues. For former marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe, it was “No limits.” For 2:20 marathoner Sara Hall, it’s “The well is deep.” And for legendary professional cyclist Jens Voigt, it was “Shut up, legs!” Such phrases counteract the panic reflex that threatens to control our thoughts and actions in difficult moments by providing an alternative reflex, not unlike how the mnemonic “Stop, drop, and roll” has saved the lives of many a person whose clothing’s caught on fire.

The options are endless: “Never give up.” “No excuses.” “Be brave.” The more personal your chosen accountability cues are—the more they come from the heart, in other words—the more effective they will be in holding you to the standard you’ve set for yourself. My mantra for my second Ironman was “Don’t panic,” a choice I made based on the fact that I had hit the panic button more than once in my first Ironman and on the expectation that I would face the same temptation again. Sure enough, I did, but the words I had prepared in advance kept me from repeating the mistake I’d made seventeen years before.

With few exceptions, runners who truly, deeply want to be tough use accountability cues in hard workouts and races. All runners engage in some form of self-talk while running, but whereas in the minds of runners who struggle with pacing, self-talk often takes the form of an unstructured shouting match between base instincts and their best self, pacing masters put their best self in charge before the battle even begins through accountability cues.

Limit Testers

Training is more than a vehicle for building fitness. It is also a potential vehicle for building toughness. Each run you do should have a specific fitness-building purpose, but a select few workouts should be set aside for the special purpose of suffering for suffering’s sake. I call these workouts limit testers.

A well-designed limit tester subjects the runner to intense suffering but is not so punishing that it does more harm than good physically. This balance can be achieved through workout formats that require you to run as hard as you can for short periods of time. There are two basic ways to run to your limit, both of which were first discussed in Chapter 2: closed loops and open loops. Closed loop limit testers are runs or run segments with a definite endpoint that are intended to be reached at a maximum effort. Open-loop limit testers are runs that continue to the point of failure.

An example of a closed-loop limit tester is a set of six, one-mile repetitions where the first five are run at 10K pace and the last mile is completed as fast as possible. Another example is long accelerations, in which runners gradually accelerate from a jog to a full sprint over the course of several minutes. An example of an open-loop limit tester is the Prefontaine, where runners complete alternating 200m segments at one-mile race pace and one-mile race pace plus 10 seconds per 200m until they can no longer hold the required paces. All of these limit testers are included in the training plans at the back of this book and also in the library of workouts available at 8020endurance.com/on-pace-workouts.

Limit testers build toughness in two ways. First, they increase tolerance for the type of discomfort that is experienced in maximal running efforts. This was demonstrated in a 2017 study led by Thomas O’Leary of the UK Ministry of Defense, which found that subjects who completed either six weeks of moderate intensity training or six weeks of painful high-intensity training experienced similar improvements in aerobic fitness, but the latter group showed significantly more improvement in an open-loop time-to-exhaustion test and a test of pain tolerance. The second way in which limit testers increase mental toughness is by enhancing self-efficacy. Runners who routinely make the choice to subject themselves to intense discomfort in workouts come to see themselves differently than those who do not. Specifically, they see themselves as being capable of choosing to hurt in pursuit of their running goals. As runners move toward pacing mastery, their running experience seems less like something that is happening to them and more like something they are making happen. Limit testers contribute to this wonderful feeling of running free.