Having skinned my knuckles trying to de-ice the car windscreen this morning with a debit card, I think it’s safe to declare that winter has well and truly arrived (here in the Northern hemisphere at least). As the air temperature drops you can bet your bottom dollar that an increased number of us will be missing training sessions with coughs, colds, sore throats and the flu.

Despite having put a man on the moon, inventing the iPhone and discovering the Higgs Boson, I find it a bit weird that we still don’t fully understand exactly why we always see a rise in upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) around this time of year.

What’s actually more useful to athletes is understanding what they can do to minimize their chances of getting ill so that their training can go on largely uninterrupted over winter.

Just how susceptible are athletes to getting sick?

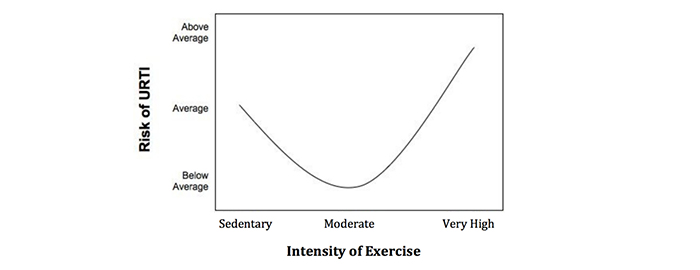

There’s a long standing and widely held (though not fully proven) belief that exercising has a ‘J’ shaped effect on the immune system and, by extension, on your susceptibility to picking up infections and illnesses.

The graph below (taken from a 1994 paper on the subject) illustrates this idea nicely:

The theory goes that when we do some moderate exercise our chance of catching URTIs drops (presumably because of the positive effects light exercise tends to have on our overall health).

However as exercise intensity or training load increases beyond a certain point, our risk of getting ill actually increases. It can even begin to exceed the risk associated with doing no exercise at all.

In other words, athletes training lightly are better protected from coughs and colds than couch potatoes. But those training very hard run an increased risk of getting sick.

It’s thought that this is because demanding training creates physical damage in the body, which in turn causes a range of stress responses that leave the immune system compromised and our bodies more “open” to the infections, germs and viruses that we inevitably encounter in day-to-day life.

Depending on the level of stress induced by a bout of exercise, it’s thought that the “window of susceptibility” can last anywhere from three to 72 hours after training or competition.

From personal experience I’m convinced that I’ve experienced this ‘J curve’ in action many times. I am (and always have been) way more susceptible to illness immediately after times of high stress—be that in the form of heavy training, big races, periods of stress at work or lots of back-to-back, long-haul travel. Conversely, I seem to be way more resilient when I’m just ticking over with a nice, low level of training.

And there’s data to back this theory up too. For example, a study of participants in the LA marathon in 1990 showed that significantly more of those who competed in the race got a cold in the days after finishing than in a control group of runners who didn’t take part in the race.

What can you do to minimize your chances of getting ill?

Any war against illness ultimately needs to be fought on two fronts by athletes to be effective:

- Minimizing exposure to potential sources of infection (especially at times when the immune system is likely to be compromised).

- Keeping the immune system as strong as possible to give it the best chance of fighting off any infections you do come into contact with.

Minimizing Exposure

Minimizing your exposure to sources of infection primarily involves a lot of relatively simple and repetitive common sense safeguards including:

- Avoiding contact or proximity to those who are obviously ill (runny noses, coughs, sneezing).

- Regular hand washing and good personal hygiene.

- Avoiding sharing cups/water bottles and cutlery.

- Steering clear of crowded areas such as public transport during rush hour.

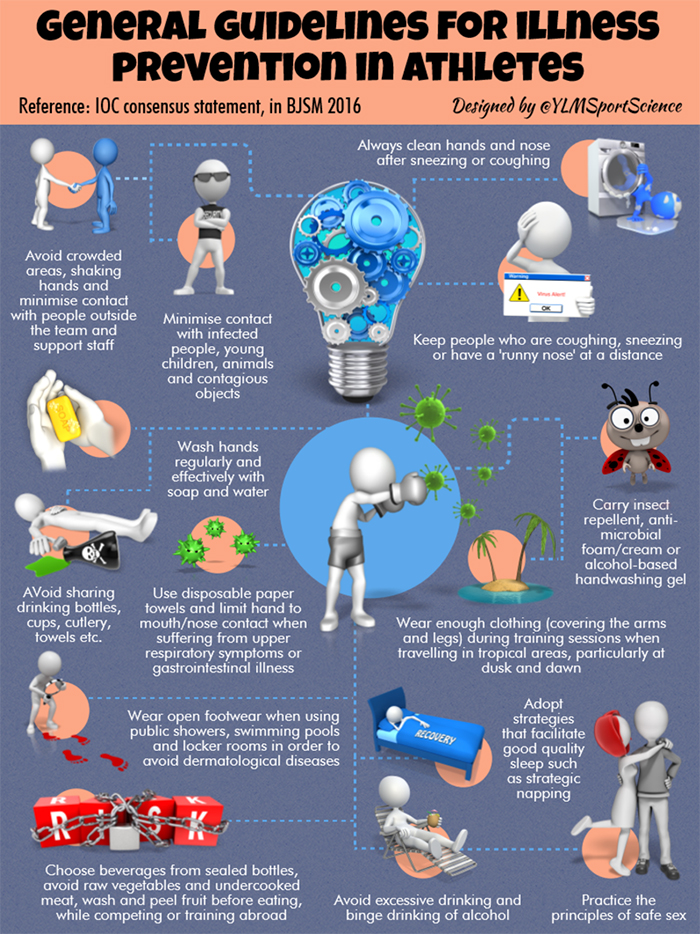

These guidelines were taken from a very recent International Olympic Committee consensus statement on the subject and they’re summarized neatly in the below infographic by Yann LeMeur ( who is worth a follow on Twitter if you’re looking for good summaries of the latest sports science research by the way):

Although this might be stating the obvious, I think it’s worth emphasizing that taking these precautions are especially important at times when your immune system is likely be at its most vulnerable, such as immediately after hard workouts, races and during extended blocks of training.

Smashing out a hard interval session shortly before jumping on a packed rush hour train to work might not be the best idea if you’re aiming to minimize your chances of getting ill. Finding more sensible times to do your hardest workouts (where you can plan in some recovery time immediately after) instead could pay dividends by enabling consistency in the long run.

Keeping the Immune System Strong

There are a number of key areas that come up in most experts’ recommendations for keeping your immune system strong. Many revolve around minimizing your body’s stress responses:

Get Enough Sleep

A good 8 hours of quality shut-eye every night is a cornerstone of solid recovery and recuperation for all athletes. Naps and power naps during the day are also great if you have time to fit them in.

If you’re suffering with unavoidably disrupted sleep patterns it’s important to consider modifying your training plan to make it less stressful (i.e. shorter and less intense sessions), especially on days when sleep has been compromised the night before.

Get Your Nutrition Plan Right

It’s a bit of a wishy washy and overused term but maintaining a good balanced diet is critical for keeping your body healthy and keeping unnecessary physiological stress to a minimum.

It’s also very important to fuel your training sessions and competitions with adequate carbohydrate intake to avoid bonking (hitting the wall and running out of glycogen), as doing so has been shown to increase the levels of stress imposed on the body.

This subject was tackled in a 2004 paper which concluded that taking in 30g to 60g of carbohydrate per hour during hard endurance training appeared to reduce the levels of the stress hormone cortisol released during and after training. It also decreased measurable levels of immunosuppression in athletes undertaking “sustained intensive exercise,” so it seems that it would reduce your window of susceptibility to infection too.

Manage Your Overall Training Load

Because a high training load is stressful on the body (the goal being to drive positive adaptation), careful planning and management of your program can help to maximise those adaptations whilst minimizing the chance of getting ill.

Take these guidelines into consideration while planning your training program:

- Building in a sensible progression of volume and intensity over time rather than ramping training up too quickly, which can leave you excessively tired and cause elevated body stress levels.

- Planning your hardest training at times when you’ll have the best chance to maximize recovery afterward and when other life stresses are low.

- Having regular rest days in your program and planning in proper recovery weeks during your training cycle.

- Working with a coach or mentor to help you work out your plan and get a second opinion on how much load to take on as well as how to progress that over time.

Monitor for Signs of Overtraining

It’s a great idea to record things like morning resting heart rate, mood, performance and motivation in a training diary. If you record these metrics accurately and learn to read the signs your body gives you, this kind of information can act as an early warning system for when you’re starting to get tired and run down.

It’s then possible to modify training to back off the intensity or duration (or rest up completely) and avoid really running yourself into the ground. This is a huge problem in highly motivated athletes. I remember as a young triathlete regularly trying to push through excessive tiredness and fatigue and ending up training myself into illness many, many times. This is another area where working with an external coach or mentor can really help as they can often look at what you’re doing from a less emotionally involved point of view and tell you to back off before you’d be willing to do so if left to your own devices.

Hydration

Good hydration plays a couple of supporting roles in maintaining the immune system.

The first is that—believe it or not—your saliva and snot form a critical part of your body’s first line of defense against infection. They contain antibacterial enzymes that help kill off germs before they get a chance to enter the body. As dehydration can compromise the production of these fluids, it can lower this first line of defense.

Also, in the same way that running low on glycogen can increase general stress levels in the body, so can being chronically dehydrated. As such, the maintenance of a good hydration status helps keep your body happy and reduces the overall stress it’s under, keeping the pressure off your immune system as much as possible.

These are a few ideas to help you avoid unnecessary illness during this winter training period. Of course, none of these tips are a magic bullet for staying healthy (as, sadly, there’s just no such thing), but when taken as a whole and applied methodically they ought to give you a decent chance to stay healthier and hit 2017 in good shape.