There are many reasons to continue to train and race after the age of 40, well into your 50s, 60s and beyond. The theory that making athletic gains after 40 is a much greater task than it is in your 20s may not be as accurate as once thought. Sure, it is going to be a little harder, but as science and race results show, your potential for making gains as a masters athlete may be more achievable than you realize.

There are many reasons to continue to train and race after the age of 40, well into your 50s, 60s and beyond. The theory that making athletic gains after 40 is a much greater task than it is in your 20s may not be as accurate as once thought. Sure, it is going to be a little harder, but as science and race results show, your potential for making gains as a masters athlete may be more achievable than you realize.

It is well accepted that peak performance as an endurance athlete seems to occur somewhere between 25 to 35 years of age1 – a theory easily demonstrated with results from any major competition. But what happens after our peak performance years have passed? How long can we maintain a high level of fitness, or at the least, continue to make gains towards greater levels of fitness as we age?

Studies show that declines in performance are going to happen, with an approximate 10% decline in VO2 max from the years 35 to 55 years of age2. But not all studies take into account changes in lifestyle, motivation levels, injury and many other factors. A study done on masters runners between the ages of 50 and 82 years of age, who continued to compete on a regular basis over a 10-year period of time, showed less declines in VO2 max compared to their non-competitive counterparts3. Studies also show that a slight decline in VO2 max may be countered by the ability to deal with greater amounts of lactic acid, an advantage found to exist in older runners2. This could possibly explain why many endurance athletes in their late 40s and 50s are still competitive with athletes in their 20s and 30s.

You can expect to see fast finish times from top pros in their 20s and 30s in the results of any endurance event, but now it’s also common to see athletes in their 40s and 50s almost as fast, if not at times faster. For example: the 40-44 year-old male category winner in the 2012 Boston Marathon finished in 2:23:08, just 10:28 behind the overall winner, making him 15th overall. In Ironman events, the top 40-50 year-old finishers consistently place in the top 20-50 overall, out of thousands of participants. Even the winner of the 50-54 year-old category of the 2011 Ironman Lake Placid placed 47th overall. Now that is impressive!

When I think about great athletes in the masters age range who can compete and win against their younger elite counterparts, I think about Ned Overend and Tinker Juarez. Ned Overend has been racing bikes since the mid 70s and has lead a very successful career as an endurance athlete. He was the World and National Xterra Champion from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. At the age of 55 in 2011, he won the Iron Horse Classic, a professional road race from Durango to Silverton, Colorado, against top-level riders in the pro field.

Tinker Juarez is a two-time U.S. Olympian, three-time U.S. national XC champion, and has had countless wins as a professional since 1974. In 2010, Tinker was named MTB world master champion, and in 2011 at the age of 50, he placed 31st out of 104 starters in a very elite pro field at the Sea Otter Classic XC race. Both Ned and Tinker are elite athletes, but both are great examples of the ability to maintain a very high level of fitness as they age.

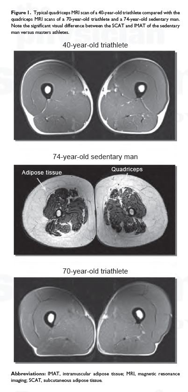

Race results are not the only reason to maintain an active lifestyle as you age. Maintaining good health and fitness is probably the most important goal to keep in mind. A 2011 study examined 40 athletes aged 40 to 81 to answer the question, “What really happens to our muscles as we age if we are chronically active?” Subjects in the study trained consistently (about four to five times a week) for competitions in various sports such as cycling, running, and swimming. This study shows that we are capable of preserving both muscle mass and strength with lifelong physical activity. The study also demonstrated the retention of muscle strength as we age (pictured to the right, MRI scans of quadriceps; ref 4). The athletes studied showed that peak torque measurements did not decline until ages 60-69, and no significant difference in peak torque measurements were observed among the 60, 70, and 80 year-old groups. So, although peak torque showed a decline around 60 years, there was little decline in strength with further aging4.

Race results are not the only reason to maintain an active lifestyle as you age. Maintaining good health and fitness is probably the most important goal to keep in mind. A 2011 study examined 40 athletes aged 40 to 81 to answer the question, “What really happens to our muscles as we age if we are chronically active?” Subjects in the study trained consistently (about four to five times a week) for competitions in various sports such as cycling, running, and swimming. This study shows that we are capable of preserving both muscle mass and strength with lifelong physical activity. The study also demonstrated the retention of muscle strength as we age (pictured to the right, MRI scans of quadriceps; ref 4). The athletes studied showed that peak torque measurements did not decline until ages 60-69, and no significant difference in peak torque measurements were observed among the 60, 70, and 80 year-old groups. So, although peak torque showed a decline around 60 years, there was little decline in strength with further aging4.

In conclusion, declines in performance are inevitable, but the rate of decline may be much slower than once believed. The increasing amount of research and results from masters age athletes continues to support the theory that we can all make gains, reap great health benefits and maintain a high level of fitness over the age of 40. Never let your age stop you from pursuing greater athletic goals.

References

Tanaka, H. & Seals, D.R. (2008, January 1). Endurance exercise performance in Masters athletes: age-associated changes and underlying physiological. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17717011/

Peiffer, J.J. et al. (2008, September). Physiological Characteristics of Masters-Level Cyclists. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18714246/

Pollock, M.L. et al. (1987, February). Effect of age and training on aerobic capacity and body composition of master athletes. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3558232/

Wroblewski, A.P. et al. (2011, September). Chronic Exercise Preserves Lean Muscle Mass in masters Athletes. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22030953/