In August, the western United States plays host to some of cyclings hardest races, the Larry H. Miller Tour of Utah and the USA Pro Challenge. These races offer up some of the most climbing you will find in a 7 day stage race, but it’s an invisible object that makes these so tough. These races are held at some dizzying heights, often at 10,000 ft or higher.

Effects of Cycling at Altitude

As you gain altitude, there is a reduced amount of pO2 (partial oxygen pressure), meaning that there is less oxygen for your blood to carry to your muscles. The USA Pro Challenge takes place mostly above 7,000 ft and at that altitude the body will take in at least 25 percent less oxygen per breath because of the reduced amount of pO2 in the air when compared to sea level. With less oxygen available to deliver to the muscles, riders will see a decrease in performance when compared to lower altitudes.

The effects to your body when racing at altitude are higher heart rate and lower power output. Since you are getting less oxygen to your muscles your body increases it’s heart rate to help bring in more oxygen which means you reach your max output quicker. This leads to a lower Functional Threshold Power (FTP) and also makes it harder to recover from maximal efforts.

Acclimating

In preparation for these events, many racers have arrived in Utah and Colorado well in advance to help acclimate to the altitude. Since there is less oxygen being delivered to the muscles the body will produce more red blood cells which deliver the oxygen to the muscles. By spending this extra time at altitude the racers will have more red blood cells and become more acclimated which will lead to a lower drop off rate in power at higher altitudes.

Many riders will take this approach when preparing for any race. They will have specific altitude training camps. By spending more time at higher altitudes they can increase their red blood cells, allowing them to make longer and harder sustainable efforts at lower altitudes. But they will only want to stay up for three to four weeks. Any longer than that and they will begin to lose muscle from riding at the lower power outputs. There are other methods as well such as training low sleeping high and training high sleeping low.

Calculating Available Aerobic Power at Altitude

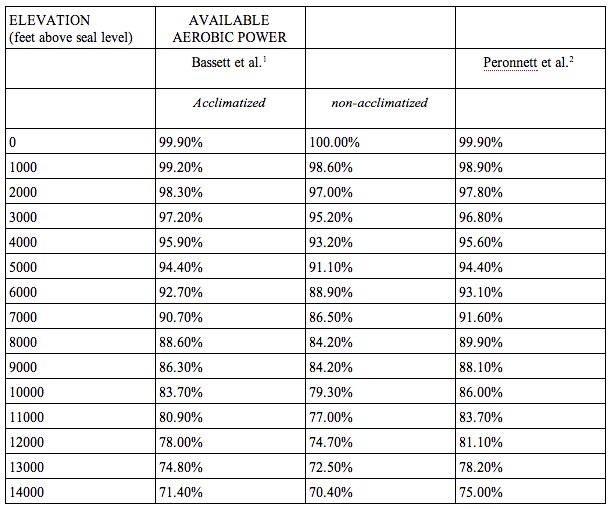

The following equations — generated from a study conducted on four groups of highly trained or elite runners — can be used to estimate aerobic power at a given altitude as a percentage (y) of what is normally available at sea level, where x = elevation above sea level in km.

- for acclimatized athletes (several weeks at altitude): y = -1.12×2 – 1.90x + 99.9 (R2 = 0.973)

- non-acclimatized athletes (1-7 days at altitude): y = 0.178×3 – 1.43×2 – 4.07x + 100 (R2 = 0.974)

Another study created the following equation.

- y = -0.003×3 + 0.0081×2 – 0.0381x + 1

Here is a table derived from these equations:

Applying Power Adjustments When Cycling at Altitude

Racers in the USA Pro Cycling Challenge will all be aware of the effects of racing at altitude. Racing with a power meter has become very popular, but racing at altitude throws out every number they have used all year. They now have to readjust their FTP, pacing strategies, and be careful not to attack too often or dig too deep to stay with riders surging on the climbs. With the reduced amount of oxygen being delivered to the muscles, it becomes harder to catch your breath and recover.

For example, take an athlete who at sea level has a 380 watt Functional Threshold Power. If they want to use their power meter to set a pace for the Vail TT, they could be looking at trying to average only 335 watts. This is taking in a drop of their FTP by 16 percent because of the altitude while being able to race at 105 percent since the effort will only last around 25 minutes. Another example is when they are climbing up the 11,000 foot Monarch Pass, they may be riding full gas at 310 watts because of the altitude.

Altitude creates yet another variable in the already complex world of bike racing. The reduction in available oxygen creates a series of physiological issues. While riders can do some work to prepare for racing in thin air, much of it comes down to proper pacing and knowing the limits.

References

Bassett, D.R. et al. (1999, November). Comparing cycling world hour records, 1967-1996: modeling with empirical data. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10589872/

Péronnet, F. et al. (1991, January). A theoretical analysis of the effect of altitude on running performance. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2010398/