It’s possible that I was already infected with the coronavirus when I ran the Atlanta Marathon on February 29, 2020. What I know for sure is that, infected or not, I wasn’t symptomatic yet, and, in fact, I performed quite well, finishing 15th overall and winning the men’s 45-49 division. But a few days after I returned home to California, I developed a tickle in my throat, which soon evolved into a full-blown respiratory illness. Never before had I been so sick for so long. My most bothersome complaint was an incessant dry cough that, at its worst, was so violent I frequently hacked up bile and blood and even tore cartilage in my ribs during one particularly awful barking fit.

It took me a full month to feel ready to try a cautious test run. It went okay, and within a few weeks, I was back to full fitness — alas, not for long. On October 6 I had an unexpectedly bad workout, abandoning a set of 600-meter intervals when I couldn’t hit my target times. In hindsight, I see this aborted training session as the first indication that I had developed long COVID, a chronic condition affecting an unlucky fraction of individuals who contract the coronavirus. Symptoms vary from person to person, but among the most common and debilitating are fatigue, shortness of breath, and brain fog, all of which I have to this day.

Worse, in February 2021, I was diagnosed with heart disease, and although it is impossible to know whether COVID caused or contributed to this condition, it is well established that COVID-19 increases the likelihood of subsequent cardiovascular diagnoses. While doctors have since cleared me to exercise, it’s moot at this point because my long COVID symptoms — which also include exercise intolerance and post-exertional malaise (i.e., the worsening of symptoms following even minor physical or mental exertion) — remain so severe that it is impossible for me to do anything more intense than walking without ending up bedridden for days or even weeks afterward.

I’m telling you all of this not to elicit sympathy or to frighten you but to give you a concrete example of what the coronavirus can do to an otherwise healthy endurance athlete. The risks are both real and serious, and while it’s too late for me, I feel compelled to do what I can to help other athletes avoid ending up like me. I do so not as a doctor or scientist, for I am neither, but as a coach. The advice I offer here on mitigating COVID-related risks is the same counsel I give the athletes I coach. In fact, one of my athletes, Kathleen, picked up the virus around the time I started working on this article, so I will illustrate current best practices through her example. First, we’ll talk about mitigating risk before infection, and then we’ll discuss what to do after you get infected.

How to Best Avoid COVID Infection

An ounce of prevention, as they say, is worth a pound of cure. The most effective ways to minimize any negative effects of the coronavirus on your health and fitness are to avoid getting infected in the first place and to take preemptive steps to ensure that if you do get sick, you don’t become seriously ill.

Wear a Mask and Steer Clear of Large Gatherings

You’ve heard the experts’ recommendations on avoiding infection a thousand times, but I’ll repeat them here for the record: steer clear of large gatherings in indoor spaces. When you do find yourself in such an environment, try your best to maintain two meters of separation between yourself and other people and wear a medical-grade face mask when case levels are high in your area and indoor mask-wearing is either required or recommended. Wash your hands frequently and avoid touching your face.

Minimize Human Contact Before and After Hard Workouts

All of these guidelines apply to both athletes and non-athletes. One additional recommendation that is athlete-specific is minimizing contact with other people before and after hard workouts and races. Whereas exercise generally strengthens the body’s immune defenses, exhaustive exercise temporarily suppresses immune function, opening the door for viruses to gain a foothold in the body. It’s conceivable that I would not have gotten sick after my trip to Atlanta if I’d traveled there for a purpose other than running a marathon.

Prioritize Sleep and Nutrition for Immunity

Other stressors besides exhaustive exercise, such as lack of sleep and work stress, also compromise the body’s immune defenses, whereas good nutrition has the opposite effect. A useful way to think of these lifestyle factors is that anything you might do to promote recovery from training you should also do to protect yourself from getting sick. This means meeting your sleep requirements routinely, incorporating rest and relaxation into your daily routine, and maintaining a balanced diet that is rich in plant foods and low in processed foods. A study in the British Medical Journal reported that plant-based and pescatarian diets were associated with lower COVID-19 severity among healthcare workers in six countries.

Stay on Top of Vaccines and Boosters

The surest way to minimize the severity of illness in the event you are infected is to get vaccinated and stay current on available booster shots. According to the most recent data, the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna each reduced the risk of covid-related hospitalization by 94%. Immunization itself is not without risks, but they are minuscule in comparison to those associated with remaining unvaccinated. For example, roughly one in one million individuals who receive the Johnson & Johnson vaccine develop blood clots. The coronavirus itself, however, increases the risk of venous blood clots by 500%.

My athlete, Kathleen, has followed all of the above recommendations, and has been rewarded for it. She made it 30 months into the pandemic before getting infected, and because she’d received her second COVID booster just two weeks before her exposure to the virus, she had a very mild case.

What to Do After COVID Infection

Experts say that everyone will get the coronavirus sooner or later, no matter how precautious they are, as Kathleen’s example demonstrates. Athletes, therefore, need to understand how to respond when the inevitable transpires. Fortunately, we know a lot more about what athletes should (and should not) do after either testing positive or developing symptoms than we did when I got sick.

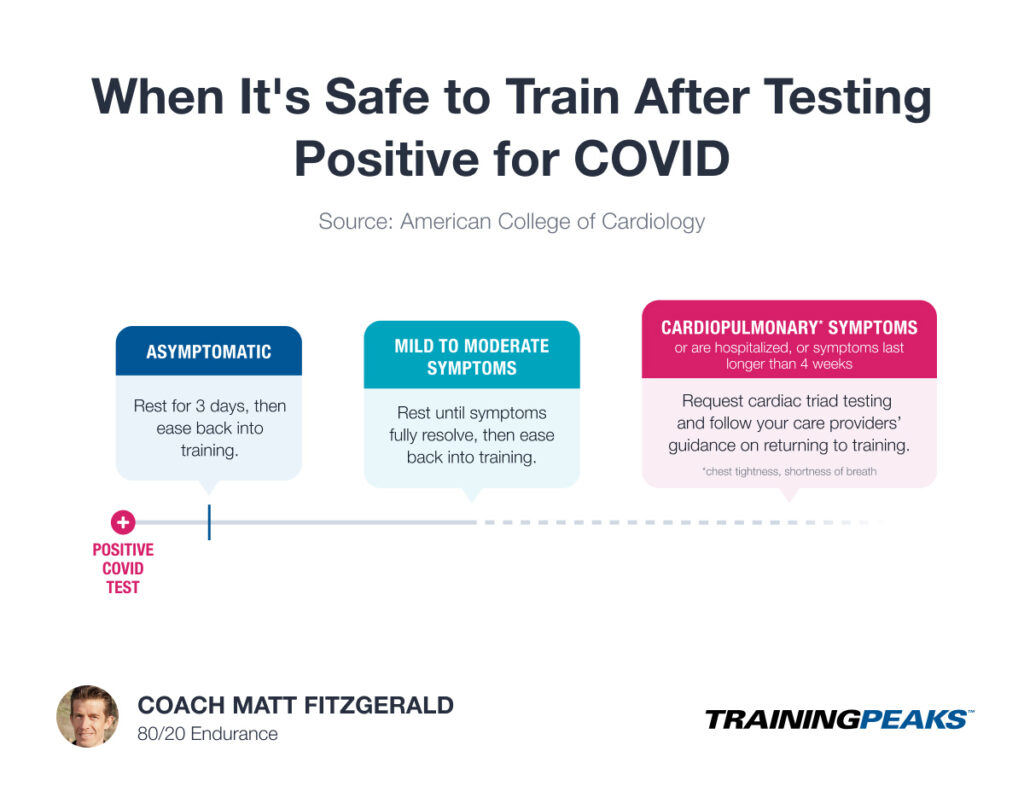

In my one-on-one coaching work, I currently use the decision tree created by the American College of Cardiology as part of its COVID-19 “return to play” consensus statement (visualized above). You can access it here, and I encourage you to do so, but here’s a brief summary of the main points:

- If you test positive and are completely asymptomatic, rest for three days and then ease back into training.

- If you experience mild to moderate symptoms, rest until these symptoms fully resolve and then ease back into training.

- If you experience cardiopulmonary symptoms (e.g., chest tightness, shortness of breath), are hospitalized, or have symptoms lasting longer than four weeks, tell your doctor and request cardiac triad testing (ECG, cTn, echocardiogram), then follow your care providers’ guidance on returning to training.

Watch Your Data in TrainingPeaks

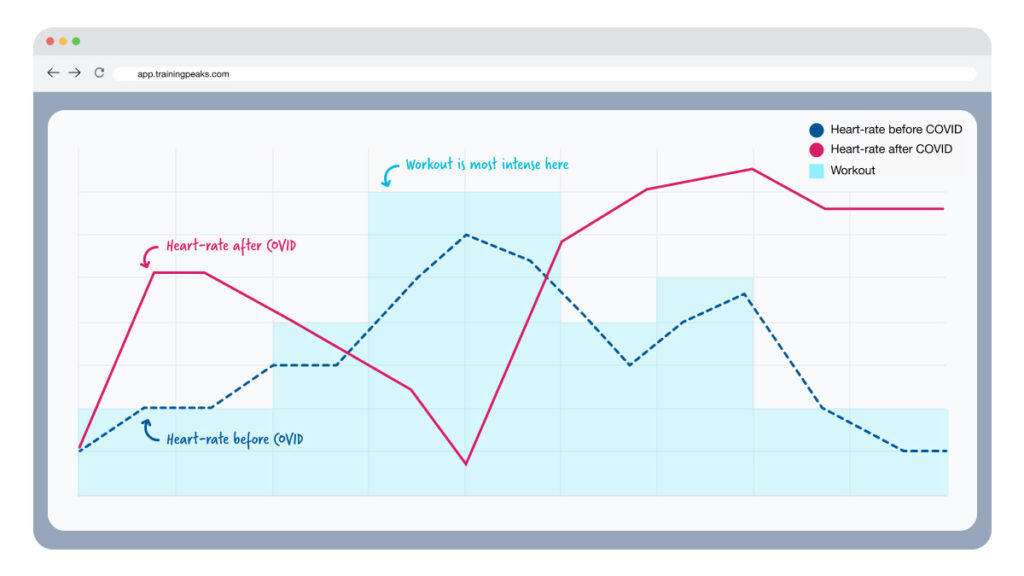

Pay extra attention to your heart-rate data in your workout uploads to TrainingPeaks post-COVID. Look for patterns that seem out of the norm for you compared to your training before infection (as illustrated below). Even before I started to experience long covid symptoms outside the exercise context, I noticed odd behavior in my heart rate — which sometimes dropped when it should have risen (as when I ran uphill) and rose when it should have dropped (as when I stopped at an intersection) — during exercise. Don’t be alarmed by any little anomaly, but do be vigilant until you’re back to 100%.

Kathleen’s case was interesting. She did not test positive until three days after she developed a runny nose and a cough, but because these symptoms manifested soon after she spent time with a friend who got a confirmed diagnosis before Kathleen did, we assumed she had COVID and proceeded accordingly. Thankfully, she experienced no cardiopulmonary symptoms, so she rested until her runny nose and cough went away and then eased back into training.

The timing of Kathleen’s illness wasn’t great. Those ten days of training she missed fell between nine and eight weeks before she was scheduled to participate in the Chicago Marathon. But an athlete doesn’t lose that much fitness in ten days, and because we went by the book in handling the setback, Kathleen was 100% ready for the final push to her event. At the time of this writing, she was back to her pre-COVID training load and feeling strong. Follow Kathleen’s example in managing your own COVID risks!

References

Chukumerije, M. (2022, April 13). 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on COVID-19: Return-to-Play Take Home Points. Retrieved from https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2022/04/13/13/49/2022-acc-expert-consensus-decision-pathway-on-covid-19-return-to-play

Kim, H. et al. (2021, June 7). Plant-based diets, pescatarian diets and COVID-19 severity: a population-based case–control study in six countries. Retrieved from https://nutrition.bmj.com/content/early/2021/05/18/bmjnph-2021-000272.info