Heart rate-based training has been around for about 30 years. Power-based training is somewhat newer having arrived on the scene some 20 years ago. Speed-distances devices that measure pace have been around about 10 years. Heart rate is a good way of measuring how the workout felt; it’s a proxy for effort. We can think of this as “input.” Power and pace tell us what was accomplished in the workout or race. This is “output.” When input and output are compared we have an excellent way of measuring changes in fitness. “Efficiency Factor” and “Decoupling” use this relationship to tell us how fitness is progressing.

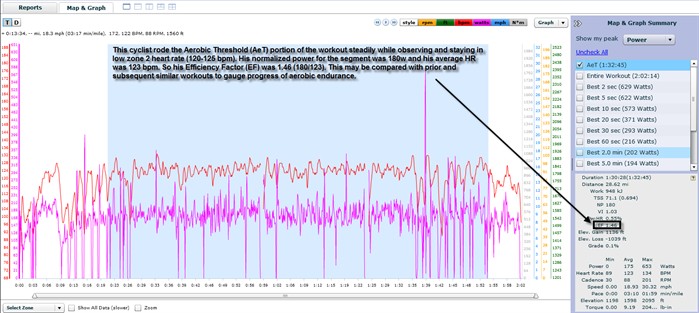

Efficiency Factor as a Marker of Aerobic Progression

We have known for decades that if heart rate during an all-aerobic (below lactate/anaerobic threshold) workout rises while the intensity (power or pace) stays the same then the athlete is not operating efficiently and his or her aerobic endurance is questionable. The same is true if heart rate stays the same and power decreases or the pace slows.

To determine EF (aka, ef factor), the software divides normalized power or normalized graded pace by average heart rate for the workout or selected workout segment such as an interval.

By comparing the resulting ratios for similar workouts over several weeks you can measure improvements in aerobic efficiency. To be reliable the workouts need to be quite similar by making sure all of the elements are alike. This includes level of pre-workout fatigue, equipment, course, weather conditions, altitude, pre-workout nutrition (especially stimulants such as caffeine), warm-up and perhaps even time of day. The more similar all of these are from one session to the next the more valuable the information is. If you are making good aerobic progress, then your EF will rise over the course of a few weeks.

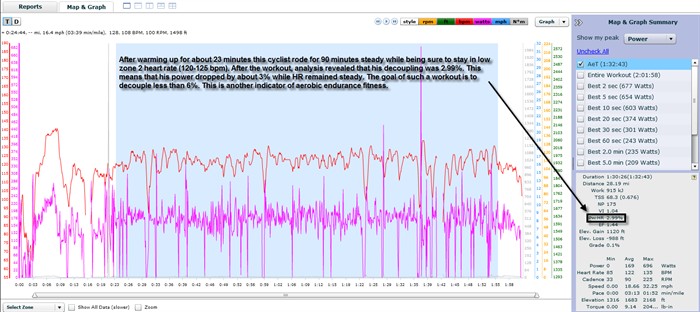

Decoupling of 5% or Less

This is a way of measuring output-input relationship changes that take place during a workout or race as a way of determining aerobic fitness. For this metric to provide useful information the workout or segment must have been fully aerobic (below the lactate/anaerobic threshold) and steady (low Variability Index).

What the software does here is compare the Efficiency Factors for the two halves of the workout or selected workout segment (such as an interval). The difference between the EF for the first half and the EF for the second is divided by EF for the first half. This produces a percentage of increase or decrease in the second-half EF.

TrainingPeaks.com and WKO+ software can help you to determine your degree of aerobic endurance conditioning by displaying and measureing your level of decoupling. I like to see athletes achieve a decoupling of 5% or less (negative numbers are, of course, less than a positive 5% and may reflect outside variables such as warm-up and weather but are assumed to be good results). As with EF, there are many variables that affect decoupling. These must be controlled. Generally speaking, if an athlete’s decoupling is consistently 5% or less for steady-state aerobic workouts then his or her aerobic endurance is sound. For example, if you quit training for a while your decoupling will reflect your loss of fitness. This will be obvious as an increase in fatigue late in the workout causing either heart rate to rise or power or pace to worsen—or both. In either case, decoupling will rise above previous values for the same workout and may result in decoupling of greater 5% indicating a need for more aerobic training.