There’s a reason many cyclists don’t make time for strength training — riding a bike is a lot more fun than pushing weights in a musty gym. However, strength training is a must if you want to continue to have fun riding and racing your bike for years to come.

Strength training can provide great performance benefits — it will make you faster in the short term, but it will also keep you fast for many years to come. In the world of masters racing, cyclists who remain youthful, vigorous, and healthy will continue to excel while many of their cohorts will start to slow down. The gym is, quite literally, a fountain of youth, and is a major key to success as a master’s racer.

Your Muscles and Aging

Your muscles put watts into the pedals — if you lose muscle, you lose power. Unfortunately, chronic muscle loss due to aging (aka, sarcopenia) can begin as early as your 30s, though the rate at which this muscle loss occurs is highly dependent upon your lifestyle. Naturally, those who are physically inactive and have poor diets will lose their muscle much faster than a healthy cyclist.

However, cycling alone will not help you preserve all of your precious leg muscle. Strength training can help counteract muscle loss in the following ways:

- Two important hormones that are key to maintaining youthfulness — growth hormone and testosterone — have actually been shown to decrease with chronic endurance training. These hormones are not only essential to building and maintaining muscle, but also enhance your ability to recover and adapt from training. While synthetic testosterone is on the banned substance list, you can legally enhance your testosterone levels by going to the gym!

- Your explosive fast-twitch muscle fibers are the most susceptible to sarcopenia. In a short duration criterium or road race, as is common in masters racing, it’s unlikely you will win without a good finishing kick. Strength training will help protect your race-winning muscles and give you the edge over your competition.

- It’s commonly known that VO2max declines with aging. However, this decline is largely due to the loss of muscle mass that occurs with aging. With less active muscle to pedal your bike, your body will not consume as much oxygen to contract your muscles. Therefore, maintaining strong muscle mass can combat a decline in VO2max.

Your Bones and Aging

Throughout puberty and into adulthood, bone mass gradually increases until it reaches its peak in your 20s. Thereafter, you must do everything you can to keep what you’ve got. Age makes you susceptible to low bone density, which can predispose you to fractures caused by frail bones — a disease known as osteoporosis. Osteoporosis affects approximately one in three women and one in five men in the United States over the age of 50.

Much research has been dedicated to assessing bone mineral density in competitive cyclists. Research has conclusively shown that chronic cycling training without any supplemental exercise can predispose you to developing osteoporosis. There are several reasons for this:

- You must place stress on your bones to stimulate growth. Cycling is a non-weight-bearing activity and will not stimulate bone growth.

- Cycling expends large amounts of energy. Combine that with a restrictive diet or inadvertent under-fueling (both common in cycling), and you’ve got the perfect recipe for a decline in bone mass.

- Loss of calcium through frequent sweating also contributes to low bone density.

These reasons, in addition to the high risk of falls inherent to cycling, create a perfect storm for bone fractures. While any sort of weight bearing activity, such as running, can stimulate bone growth, strength training will benefit your performance more than aerobic cross-training and it will also give you the bone-building benefits of other modes of activity.

What to Do in the Gym

If you’re going to invest your time at the gym, you want to select exercises that will give you the greatest benefit for both your performance and your health in as little time as possible. Large muscle group exercises that work cycling-specific muscles are the way to go.

Large muscle group exercises will work as many muscles and bones as possible while also giving you the highest post-exercise hormonal response. Squats are the quintessential exercise for cyclists. They target the muscles you need for cycling and also place load on some of the most common areas for fractures.

You will also want to select exercises to strengthen your upper body too. Bench press, shoulder press, and rows are excellent time-efficient exercises that help prevent injury and target parts of the body at risk.

However, those who are inexperienced lifters must exercise great caution, as these exercises present a high risk of injury if not performed properly. You will still reap plenty of benefits from selecting safer exercises, such as lunges and leg presses.

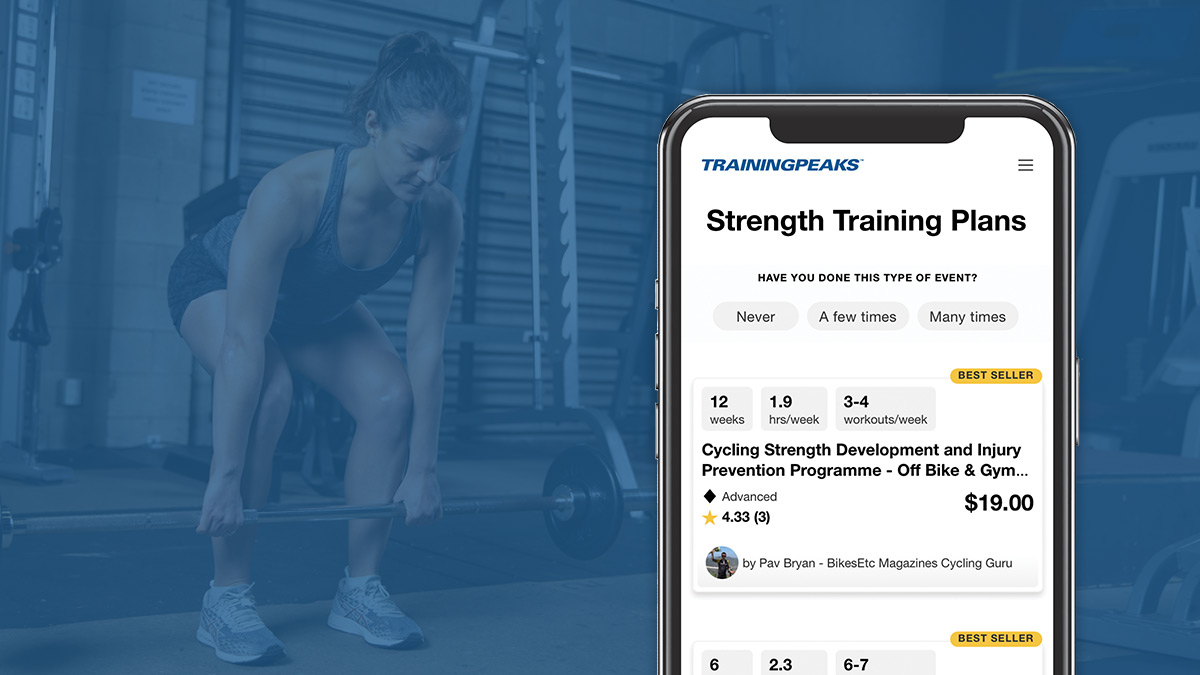

Programming strength training into a cycling program can be challenging. Strength training must be done year-round in some form and if not properly periodized, it can interfere with your bike performance. Seek out professional guidance if you are unsure of where to start.

If you want to get stronger in the gym and on the bike, contact me!

References

Abrahin, O. et al. (2016). Swimming and cycling do not cause positive effects on bone mineral density: a systematic review. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27476628/

Alemany, J. A. et al. (2008). Effects of dietary protein content on IGF-I, testosterone, and body composition during 8 days of severe energy deficit and arduous physical activity. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18450989/

Campion, F. et al. (2010). Bone status in professional cyclists. Retrieved from https://eref.thieme.de/ejournals/1439-3964_2010_07#/10.1055-s-0029-1243616

Hackney, A. C. (1989). Endurance training and testosterone levels. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2675257/

McArdle, W. D., Katch, F. I., & Katch, V. L. Exercise Physiology: Nutrition, Energy, and Human Performance. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.

Walston, J.D. (2012). Sarcopenia in older adults. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22955023/