Cortisol is the primary hormone of the stress response. When cortisol is too low, you struggle to get going. When cortisol is too high, you have trouble settling down. Thousands of years ago, cortisol mobilized energy to help us escape danger and pursue food. This effort was followed by a period of rest. In today’s chronically stressful world, cortisol dysregulation creates chronic disease. The cumulative stress of a busy life may not manifest itself in an obvious manner. Instead, it can sneak up on you and cause issues that you may not even realize are a result of high cortisol.

Here are 5 signs you might have a problem with cortisol:

- You don’t look forward to training. Once you get out there, it takes an hour to warm up.

- You have an awkward roll of belly fat that just won’t budge.

- Your energy levels wax and wane throughout the day.

- You’ve lost interest in sex.

- You have an injury ending in ‘itis.’ This suffix refers to chronic inflammation, which is a sign of a cortisol problem.

Three Main Causes of Cortisol Dysregulation

If you are suffering from a high cortisol problem, there are typically three causes. Each one is unique but has the same physical reaction.

Dietary stress

Are you on a sugar roller coaster? Your body interprets very low blood sugar (often a rebound from high blood sugar) as a threat to survival. Cortisol rushes in to save the day, telling the liver to pump out sugar. This makes you feel better initially, but if you do this too often, eventually, you’ll have a cortisol problem.

Emotional stress

Crazy deadlines, slow drivers and fighting with your partner are the classic sources of emotional stress. Too much pressure, too much anger and too many fights will give you a cortisol problem. Add a full race schedule on top, and you’ve got a recipe for burnout.

Physical stress

Meaningful training is inherently stressful. That’s the whole point of training: to stress your body, so it comes back stronger. If you train too much or too hard, you will have a cortisol problem.

What You Can Do Right Now

Thankfully, each type of stress can be managed in simple steps. Here’s how to tackle this stress and get back to health:

Check Your Diet for Excess Sugar and Starch

This step resolves a myriad of common health complaints, in addition to achieving optimal body composition and fat adaptation. Try testing your blood glucose. First, buy a blood glucose meter, which can easily be found on Amazon. Usually, the starter kit comes with 10 strips, but you might want to buy some extras. Next, check your fasted morning level, which according to the Center for Health Research, should optimally be 85 mg/dL or less. You can also check right before eating and then 30 and 60 minutes after.

These times are of particular interest, but in general, you’re looking to maintain stability in the 80 – 90 range. Does it matter that it’s 92 every time you take a reading? No, absolutely not. What you’re trying to achieve is overall stability. If you are consistently seeing spikes up and over 118, then you’re likely eating too many carbohydrates in one sitting. You may still be able to eat that many carbs, just not all at once. Reduce the number of carbs and add more healthy fat, like an extra avocado, or gobs of coconut oil, grass-fed butter, tallow, bacon grease, or MCT oil.

Get a Coach and Make a Plan

Go hard on hard days and rest even harder on rest days. You’re motivated and driven, and the lure of competition and training is intense. It’s a big part of what makes you an athlete. For this reason, you simply must have a coach, someone you respect and who is capable of drawing appropriate boundaries. Ideally, this person will be well versed in the physical signs of overtraining and lay their eyes on you on a regular basis.

Heart rate variability is a simple and grossly underutilized way to measure your readiness to train. If you own a smartphone and a Bluetooth-compatible heart rate strap, you’re ready to start tracking. My favorite app is called EliteHRV.

Meditate Daily

Visualize a leaky bucket of water. Managing stress is like managing the water level; your goal is to stop the bucket from running dry. The stress in your life is like a hole in the bottom of that bucket. Stress reduction techniques like singing, yoga and guided meditation can help you seal the hole and help prevent your bucket from running dry.

Sound fuzzy? I’ve seen the lab work showing profound improvement through simple stress reduction techniques alone. Guided meditation is clinically proven, and lucky for you, your competitors are un-blissfully unaware. If you’re new to meditation start with an app like Headspace.

Physical Interaction

Surround yourself with people you love and hug them. Have more sex. Spend more time outdoors surrounded by nature. Research has shown that physical connection, whether it be hugging a family member, having sex, cuddling a pet or receiving therapeutic touch or massage—all reduce cortisol burden and avoid burnout. Touch, love and positive social interaction act to increase the hormone oxytocin, which is sometimes referred to as the “love hormone”. Upon release, oxytocin creates feelings of contentment and calm, reduces anxiety, and increases human bonding and trust.

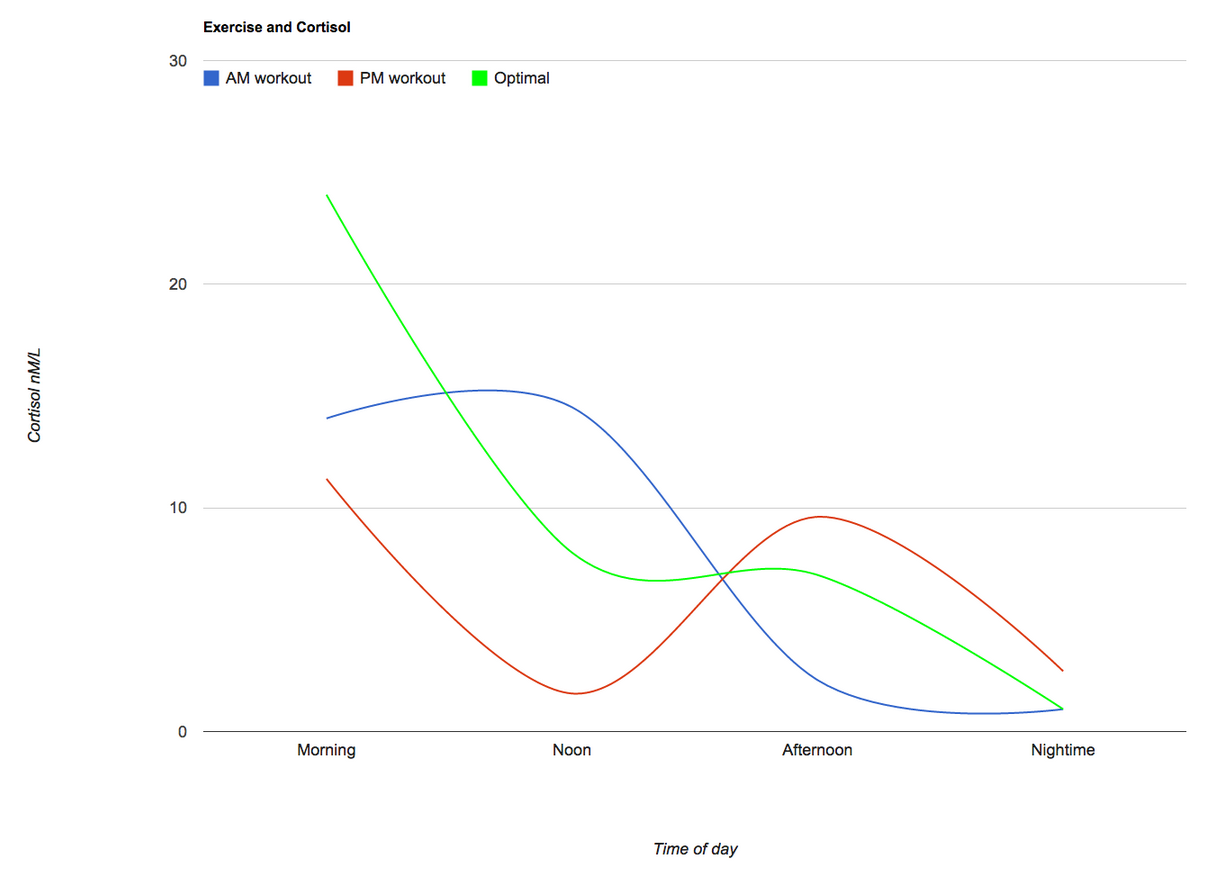

Understand how working out affects the rest of your day. Cortisol mobilizes energy and excess energy is the last thing you want late at night. Any long or intense exercise will elevate cortisol, as shown in this example:

These samples were collected on two separate days from the same very tired and burned-out person. Overall her cortisol is very low, but look what happened after the late afternoon workout. Stress and bad sleep go hand in hand.

The above tips will likely help you feel better right away. If you need more help (and who doesn’t?), we encourage you to work with a qualified healthcare professional who can administer a home cortisol test, interpret the results and help you train harder – and feel better.

References

Markus Heinrichs, Thomas Baumgartner, Clemens Kirschbaum, Ulrike Ehlert. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006322303004657

Parswani, M. J., Sharma, M. P., & Iyengar, S. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction program in coronary heart disease: A randomized control trial. International journal of yoga, 6(2), 111–117. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.113405