Training for back-to-back marathons can be a tricky endeavor. Whether that’s a Saturday/ Sunday marathon combo or marathons on back-to-back weekends, you will need to be trained and prepared. One of the critical considerations when training for back-to-back marathons is the time required to prepare adequately. If you’re well trained, you can prepare for the event with four months of training, but starting from scratch, you need at least six months of consistent training. This allows enough time to build up endurance, strength and reduce the risk of injury.

From personal experience, training for back-to-back marathons can be rewarding but requires a relatively high volume of training and a big helping of mental tenacity on race day. I’ve recorded some first-person experience in this type of endeavor, having completed three marathons in days with a group of friends in 2011.

It was an attempt to see if it was possible to complete Chicago on a Saturday, run the Indianapolis Marathon the following week and finish Grand Rapids (Michigan) Sunday. That would qualify us for the Ruthenium Level of the Marathon Maniacs with three marathons in three states in eight days. The majority of the group completed all three. I finished Chicago in 2:59, Indianapolis in 3:11 and Grand Rapids in 3:17. Thankfully, I paced a friend at Grand Rapids to a PR marathon which helped keep me motivated on a set of exhausted legs.

Let’s look at how you can have a successful weekend attempting back-to-back marathons.

Multiple Marathon Training

When we break down training, there is a lot to be said about teaching your body to recover and how to run on tired legs. There are a few critical components. The first to consider is overall volume, back-to-back long runs, double runs and workouts. Coaches must consider when building out a program to understand the physiological demands of what the athlete must endure. If we’re going to run eight total hours (two four-hour marathons back-to-back days) in 30 hours, it requires a different strategy than two marathons with 160 hours of recovery between.

The Bare Minimum

Let’s first think about the overall volume of a peak training week for someone training for back-to-back marathons. At a minimum, an athlete should be able to complete a 55-60 mile training week without significant breakdown. That week would likely consist of three weekday runs and two long runs on the weekend.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday |

| 5 Aerobic miles | Recovery | 7 miles – 4 @ tempo | Recovery | 5 Aerobic miles | 22 Aerobic miles | 16 Aerobic miles |

This is a pretty light training schedule and relies heavily on the aerobic stimulus of a weekend long run to achieve the ability to finish successfully without injury or an excessive amount of recovery time. However, a bigger story must be told if we want to maximize our ability to run back-to-back marathons quickly and efficiently.

The Break Down (Four Phases)

In a perfect world, to build fitness from scratch, you would build an athlete with a six-month lead into the race goals, with each phase building in volume, intensity and specificity. Below is a brief outline of a program for an athlete looking to run consistently at both back-to-back marathons. The first eight weeks will be redundant if your athlete is in good aerobic shape with a moderate to high volume. However, suppose you do have the time. In that case, those eight weeks can increase overall fitness at threshold, which understandably will increase the athlete’s aerobic capacity and average run speed, ultimately lowering the athlete’s race time.

Phase 1 — Build (Weeks 1-8)

The first eight weeks are dedicated to building a quality base. If starting from scratch, keep to the 10% rule for volume increases. If your athlete comes in relatively trained, focus on increasing volume and where it makes sense to; integrate double runs with 6-8 hours between. Double runs help increase capillary density, speed recovery, metabolic efficiency and mitochondrial density. Long runs should Peak at 13-15 miles on back-to-back days.

– Integrate double runs

– Increase volume

– Increase time at threshold

– Increase CTL by 2-4 points/week; track TSB to stay between -15 and -20.

Phase 2 — Extend (Weeks 9-16)

This is where you want to start getting very specific with your training demands for the races. Are the races hilly one day and flat another? Is there a significant amount of climbing or descent? Are they all road or trail? Answering these questions will help you create a program that helps build specific fitness. A hilly race Saturday means quads must adapt to the eccentric contractions of downhill running and still turn over the next day on a flat course.

If your athlete isn’t currently implementing doubles, this is a good place to integrate at least one double day per week. If the athlete cannot support the mileage, you can still increase aerobic capacity by cross-training with swimming, cycling or rowing. Cross-training is often overlooked but is the easiest way to increase training load and volume without increasing stress and pounding from running. Back-to-back long runs can get close to peak with 16-20 miles on back-to-back days.

- Increase Training Load

- Get specific with your training stimulus, hill reps, downhill work, etc.

- Back-to-back long runs are crucial

- Increase CTL by no more than four points for three consecutive weeks

- Keep Saturday TSB to no more than -20, and look at where the athlete will land Monday morning

Phase 3 — Peak (Weeks 17-20)

This is where things start to get difficult and extensive. Athletes often become very tired and fatigued, struggling to stick to a plan. As a coach, your job is to be as specific here as possible without overcooking the athlete and injuring them with too much stimulus. If you’re finding yourself battling the training schedule, be willing to pull out their doubles for two weeks and slowly reintroduce the second workout as cross-training or strength training.

Athletes are starting to conceptualize the finish line but are in the depths of training. Integrating a few marathon long run days on the weekend is smart for specific preparation at 85-90% of the goal pace. A beginner may do 26 miles one day and 10 the next, whereas a more advanced athlete may get a mental boost from flipping that to 10-13 miles Saturday and a Marathon Sunday to simulate the demands of running on tired legs. If your athlete needs to see progress, encourage them to sign up for a half or full marathon to practice fueling and hydration strategies.

- Maintain training load from Phase 2 or increase it slightly

- Get specific with your training stimulus — goal pace, nutrition plan, etc.

- Listen closely to what your athlete needs, and be willing to back off

- Keep Saturday TSB to no more than -20, and look at where the athlete will land Monday morning

Phase 4 — Taper (Weeks 20-24)

Taper is always tricky because you must balance the desire to maintain training volume while integrating recovery at the right time. What’s important here is that you need to start getting very specific with data. Planning ahead in the final four weeks to line your athlete up with a Saturday TSB of +20 to +30 is desirable. Ideally, the athlete should line up Sunday with a +5 TSB or a 0 TSB to start relatively fresh. The key to hitting this “high” of a TSB ultimately means a 14-day reduction in volume.

Your goal should be to maintain intensity while decreasing overall mileage and even limiting the athlete to one long run on the weekend 14 days out. Expect some taper tantrums from your athlete experiencing muscle soreness as they recover and super-compensate during their taper. It can’t be stressed enough; your athlete cannot go into the race too fatigued. The second day will be extremely challenging. It is always better the er on the side of caution, give full days off, and encourage cross-training and restorative practices the week leading into the race.

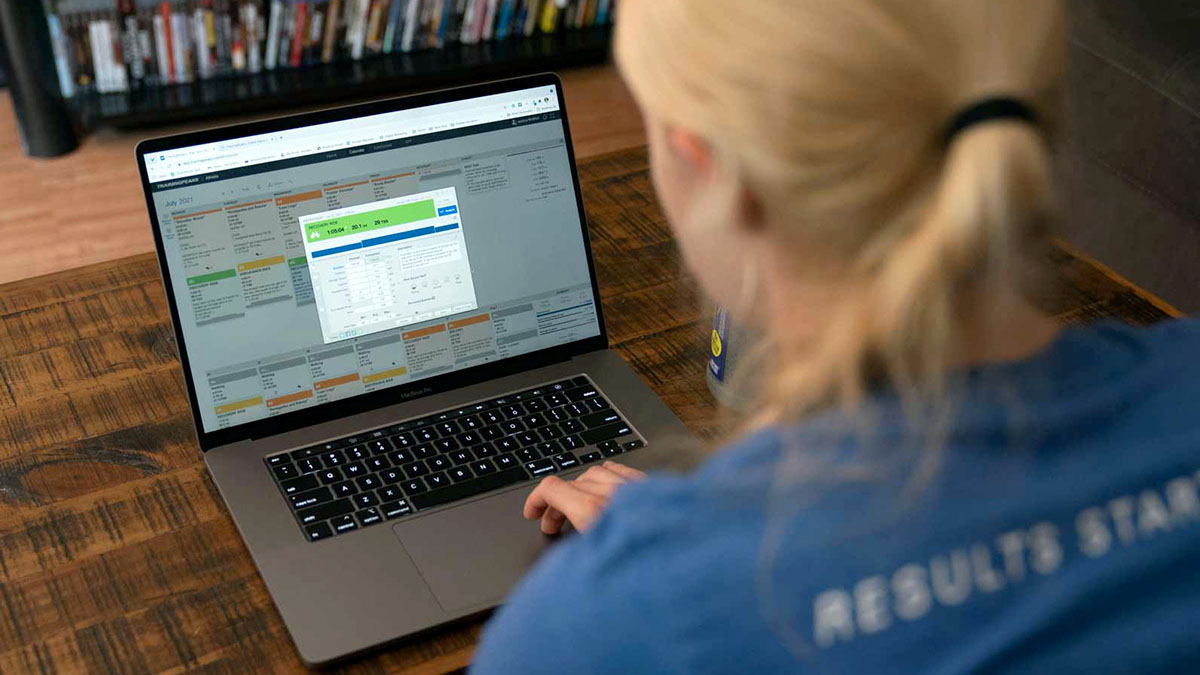

Manipulating the Metrics in TrainingPeaks

One of the best features of TrainingPeaks is the ability to forecast fitness and fatigue. This allows you to see the effects of your planned training on the athlete. Ultimately, this will enable you to create a program for ample recovery while hitting the necessary stimulus. Using an ATP to set CTL goals can help project and guide your weeks. In the ATP builder, the CTL and TSB limiters will ensure that you’re creating a program that is attainable for the athlete.

Before you get too excited, there is one limiter that can mess up all your planning, and that is making sure that you have set your athlete’s zones in the last six weeks. It is imperative that you know precisely where your athlete is starting.

Once the athlete’s zones are in place, you can move forward and make sure that you follow a few central guidelines. Athletes mustn’t have consecutive weeks where their TSB is deeper than -30. If the athlete is completing weeks with a TSB greater than -30, you need to adjust their zones immediately because they have taken a significant fitness jump. Be conscious of following an ATP or, at the very least, a consistent periodization that allows the athlete to fully recover for a week twice every block.

General Fueling Strategy

So much of the recovery equation is determined by how we fuel and recover. The same goes for race day performance and recovering for the next workout or race. We’ll discuss fueling for the event as well as fueling between races.

What an athlete fuels with is highly specific to the individual needs of an athlete and may not fall neatly into an equation where we can direct an athlete to consume X amount of gels per hour. This is also due in part to the fact that the gut is highly trainable and therefore requires the athlete to experiment with fueling rate, fuel type and a willingness to be flexible on race day.

Fueling for the Race:

Research outcomes suggest that daily dietary carbohydrates (up to 12 g·kg-1·day-1) and multiple-transportable carbohydrate intake (∼90 g·hr-1 for running distances ≥3 hr) during exercise support endurance training adaptations and enhance real-time endurance performance.

What’s important on race day is that your strategy for pacing and nutrition are the same to set yourself up for the next day. How you choose to fuel will determine if you’re set up to perform in the next day’s event. A study in 2020 found that ultramarathon athletes utilized more than just gels as fuel, including cake, fruit and mashed potatoes.

While strategies varied, athletes consumed 150-400 calories per hour, and hydration averaged 685 ml/hr or ~ 24 oz/hr. This converts to 3 ounces of water every mile if you’re averaging a 7:30/mile or 3:16 marathon pace. It’s crucial to hydrate this much, especially on Day One, because you will have less than 24 hours to rehydrate. Just to reiterate, carbohydrates are the primary source of fuel you should be focusing on.

A 2018 study showed that” 88.6% of the energy in 100-km ultra-marathon comes from carbohydrates, only 6.7% from fat intake and 4.7% from protein.” So much of the fueling strategy is about meeting the demands of the race so that you’re not behind in the race — that doesn’t mean that you should seek to replace everything you burn while racing. It simply means that you can’t dig as big of a hole on Day One of a back-to-back marathon attempt as you would if you were trying to pace yourself for an all-out effort.

Recovery

This is the most crucial part of your training, and if you can’t recover from your training, you won’t adapt to it. Therefore, anyone looking to train for back-to-back marathons must become a master of recovering from running 20+ miles with regularity.

Suppose you struggle with Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS). In that case, you may need to leverage cross-training in your schedule to diminish the impacts, improve recovery speed and maintain your training volume. Recovery, as mentioned previously, weighs heavily on diet and increasing protein and carbohydrate intake directly following long runs and hard workouts is always recommended.

General Recovery

There are so many tools, modalities and strategies to consider. The first one people forget is the structured recovery in your training program, where you might only train six days a week to ensure you’re fully recovering from the longer efforts.

When developing a recovery routine, massage tops the list because you can focus on specific areas, and it is one of the few modalities that can offer long-term benefits. Ice baths, massage guns, and compression boots are all great for acute soreness, but all pail in comparison to a healthy diet high in carbohydrates, protein, and fat.

Recovery between races

The recovery protocol between your first race and the morning of your next race is crucial. It demands that you start thinking about recovery the moment you cross the finish line of the first marathon. You should consider the first run like a workout and focus on getting in a large dose of protein and carbohydrates as quickly as you can manage to do so. Focus on managing any sore spots and if your body responds to recovery tools like compression socks, a quick shower and compression gear to limit swelling, start as soon as possible in supporting your muscles.

You should try and nap in the afternoon and take an evening walk to increase blood pressure and blood flow so you can help your body remove as much waste from that first marathon. Eating lunch with dark leafy greens in moderation can help with inflammation and recovery. Your most critical strategy is sleeping and staying mobile with a regular stretching routine every 2-3 hours to avoid getting too stiff.

On the morning of race two should bring a larger-than-normal breakfast because you will likely still be pretty famished from the previous effort. An effective training program will have you well-trained in fueling and preparing for marathon two. One thing that’s especially helpful the morning of the second race is to stretch and do a progressive walk into jog into a run for about 25 minutes to loosen the body up and get the blood flowing.

Racing Strategy for Back-to-Back Marathons

There is a lot to consider with pacing a back-to-back marathon effort. The first thing to consider is which course will require more energy. Ideally, the first course is the harder of the two races to complete, but that isn’t always easy to line up. If both courses are equally challenging, consider putting out a 90-95% effort on the first marathon, and you should be able to complete the second marathon at 87-93% of your best effort.

For example, I ran 2:59 the week before I ran 3:11 and 3:17 on back-to-back days. It may not be a perfect science, but if you can maintain a fair bit of speed work and have good running efficiency, you should be able to complete both races between 85-90% of your max on back-to-back days.

When it comes to pacing the individual races, a study in 2018 reviewed the pacing strategy for athletes racing the Spartathlon, a 246km ultramarathon, from 2011-2019 and found that of the 2598 athletes surveyed, they almost all followed a J-shaped pacing curve. This means that as they initially fatigued, they slowed and then as time progressed, they progressively increased the pace and effort of output. This study also showed similar patterns in Western States and UTMB. It shows us that we need to follow the principle I’ve coined, “the luxury of control.”

The luxury of control is about having the understanding to choose to slow down purposefully before you’re forced to slow down. This means that you are entirely in control of what’s happening and operating well within your personal running limits. It’s recommended that you pace the first race, so you finish comfortably through 20 miles, and if you feel good, you can “have fun” the last six without completely turning yourself inside out. This lines you up for a successful second day where you haven’t completely depleted your glycogen stores the day before, and you’re able to maintain your pace, although slower throughout the race. The goal (if the course allows) is to try and evenly pace the races through 20 miles and stay engaged the final 6 miles, and if you’re lucky (or been smart enough), speed up!

Racing back-to-back marathons is achievable with the proper training. The demands are like those needed to complete a 50-mile or 100-km race. What makes back-to-back marathons challenging to train for is the partial recovery achieved between the two races can make it difficult to get the legs moving on the second day, and some people can feel “locked up.”

This short recovery period is where specific training is crucial and separates a back-to-back marathon from a straight 50-mile race because the break between makes it harder to get moving and stay moving. However, once you get moving again on the second day, you can run relatively comfortably for the race as long as you stay fueled and hydrated.

Good luck if you’re considering a back-to-back marathon or training someone for one. When I completed three marathons in eight days back in 2011, it was a product of my aerobic capacity and less a product of my workouts. Earlier that year, I ran a spring marathon and trained through the summer for my first Ironman – Ironman Louisville. This certainly played into my hands because I was still very new to the sport, with my first marathon taking place in October 2009! No matter how fit you are — if you’re tackling something big in running — aerobic capacity is always your friend!