Heart rate variability (HRV) has become widely recognized as a useful way to measure recovery from endurance training, supplementing resting heart rate (RHR) and subjective wellness metrics. The basic idea is simple: measure your HRV at the same time every day whilst following your training plan. If your HRV drops significantly, it is likely that you are overloading the system. So long as your HRV recovers after a couple of days of lighter training or rest, all is well, and you can resume loading. But what if your HRV stays low, despite rest? A suppressed HRV baseline despite rest after a period of intense training can indicate Non-Functional Over Reaching (previously known as overtraining). A number of coaches rightly refer to this as under-recovery because the body is in a state of ongoing imbalance between Total Load and sufficient sleep, nutrition and stress management.

The reason that HRV can detect imbalances in training and recovery is that it taps into the parasympathetic nervous system, associated with the body’s ‘rest and digest’ mode. Being able to tap into the vagus nerve via HRV is incredibly useful and makes HRV much more sensitive than resting HR, which incorporates a mix of sympathetic, parasympathetic and hormonal influences. By tracking vagus nerve activity via HRV, you get a much earlier indicator of changes than you would by tracking HR alone. The same mechanism that allows us to listen to our body after training can also give us an insight into our general health.

Health Conditions That Affect HRV

HRV was first used medically in the 1980s to gauge the survival chances of heart attack patients brought into ICU and proved itself to be one of the most sensitive independent predictors of 24 hr survival. Since then, low HRV has been associated not only with future cardiovascular events but with all-cause mortality in several populations, including middle-aged and older men and women for instance:

- Heart attack

- Stroke

- Type II diabetes

- Heart Failure

Not only cardiovascular events but also preconditions and risk factors for these such as:

- Insulin resistance

- Atherosclerosis

- Obesity

- Hypertension / high blood pressure

- Cigarette smoking

- Mental Stress and depression

- Lifestyle factors: diet, sleep

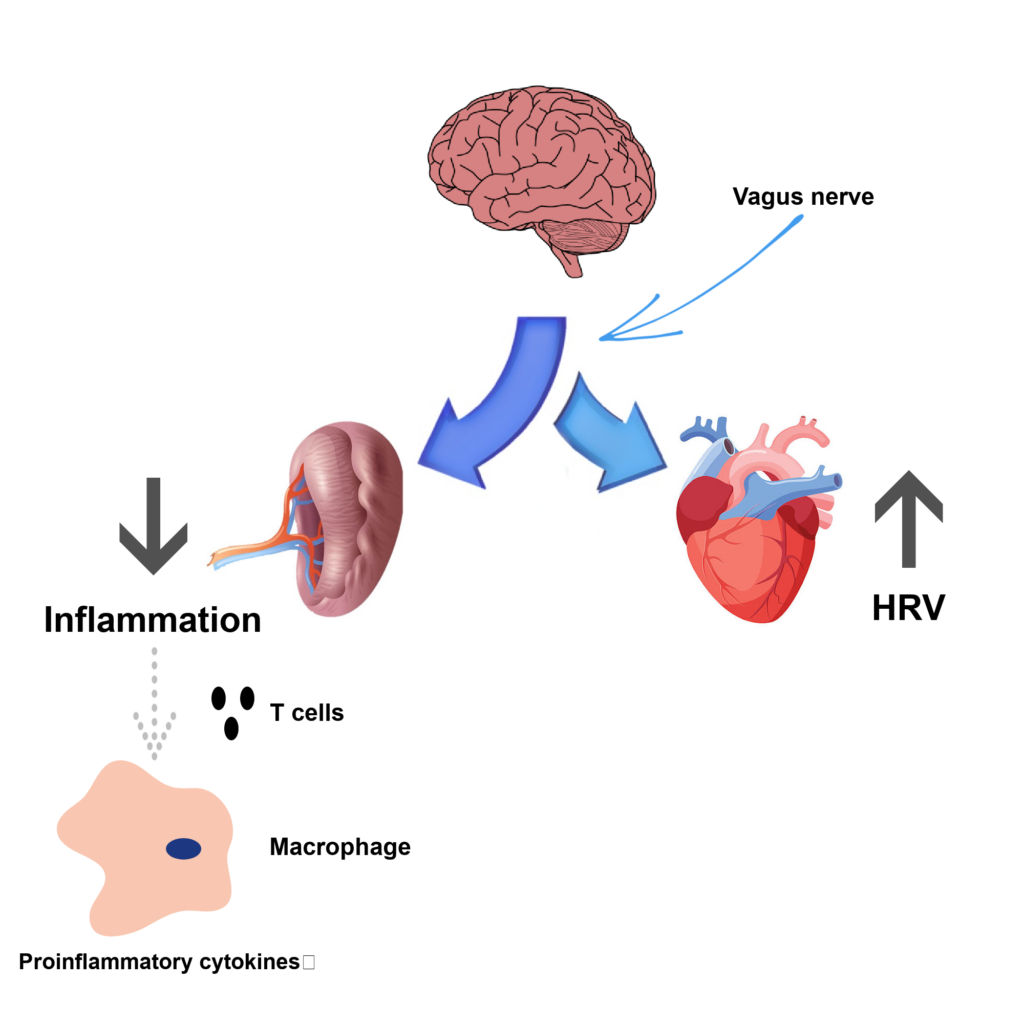

Underlying many of these health conditions is chronic inflammation. An important discovery in the 1990s relating to the action of the immune system led to a concept known as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. This mechanism gives a central role for the vagus nerve in actively restraining the immune system from excessive production of cytokines, such as CRP, IL-6 and TNF, which cause inflammation following infection or injury. Mental stress also contributes to excess cytokine production via the sympathetic fight or flight response evolved to help us get out of danger, which opposes the parasympathetic nervous system, thereby permitting the release of inflammatory cytokines. Since HRV measures the relative activation of the vagus nerve, measuring your HRV over a longer period of time could be a mechanism for gauging levels of chronic inflammation in the body. Studies to investigate the role of the vagus nerve in regulating inflammation have had mixed findings, but a 2019 meta-review supported the role of the vagus nerve in regulating and controlling the inflammatory response, as there was an overall negative relationship found between HRV and markers of inflammation.

HRV as a General Health Marker

A substantial body of research has been performed, with some clear findings, about the suitability of HRV as a marker of overall health. Let’s take a look at some of those studies.

HRV and self-rated health perceptions

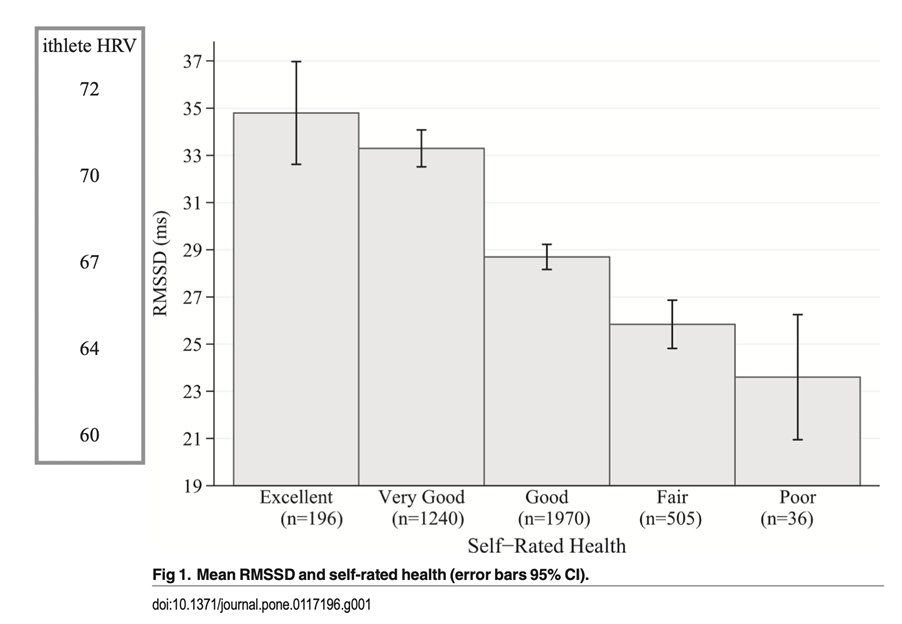

A survey of overall health across almost 4000 adults in Germany used a comprehensive lifestyle questionnaire in addition to measures of blood biomarkers, blood pressure and HRV. The study found that HRV is more strongly associated with self-rated health than inflammatory and other frequently used biomarkers. The figure below clearly shows how different overall levels of self-rated health correspond to different bands of HRV. Those who rated their health as good or very good had significantly higher HRV. The specific HRV measure used is RMSSD, also the most common one used to report HRV in apps and wearables. Although, as well as the raw scale, good software uses log transformed RMSSD, as this has better statistical properties and is more intuitive to understand (for reference, the ithlete scale = 20 x Ln(RMSSD).

HRV and hypertension

A later study by some of the same authors forecast a 50% higher chance of developing hypertension in the group with the lowest HRV (poor self-rated health) versus the group with the highest HRV (excellent self-rated health). They further concluded that a daytime RMSSD of 25ms (64 on the ithlete scale) was associated with significantly increased odds of developing cardiovascular disease.

Exercise, Health and HRV

Encouragingly, a recent comprehensive review found that multiple modes of exercise (endurance, resistance and HIIT) were all effective in improving not only HRV but biomarkers and risk factors for cardiovascular disease, with higher training intensity and frequency providing greater increases in HRV.

Another study aimed to see if there was a cut-off for intensive training, above which health benefits started to reverse. They split 1000 healthy adult participants into five groups, depending on their usual amounts of moderate to intensive physical activity per week. The lowest group performed 30 mins per day on average, with almost no HIT, whereas the top group performed 60 mins per day on average of up to 21 mins/week of HIT. The researchers found incremental benefits of increasing exercise dose and intensity on fitness markers such as VO2 max and a trend of increasing HRV (RMSSD) and decreasing resting HR, which was significant when comparing all groups. They also failed to find any evidence that exercise levels up to those of the top group were harmful to cardiovascular health.

As well as improving HRV, endurance training has been associated with reducing age-related arterial stiffness (a very important component of healthy heart aging) and improved glucose-insulin dynamics.

HRV and Weight

When it comes to weight, diet and obesity, research has found that HRV (RMSSD) correlates negatively with total body fat mass and waist-to-hip ratio (now thought to be a better measure of obesity than BMI). However, the action of dieting in order to reduce weight is stressful on the body, and HRV may drop for a period whilst the weight is being shed. It should recover, though, to a higher baseline level once the daily calorie deficit has been removed.

HRV and Differing Diets

Coverage on the effect of different diet types on HRV is not as comprehensive as we might like, but supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids commonly found in fish oils has increased HRV in studies, although some of the heart health and anti-arrhythmic benefits may be via a reduction in resting heart rate. The Mediterranean diet, which is also high in fish, as well as colorful fruits and vegetables, has also been associated with improved HRV. Minimizing consumption of refined carbohydrates and sugars (whilst ensuring the body is sufficiently fuelled for the work required) is key to maintaining healthy blood glucose levels. Insulin resistance is strongly associated with reduced HRV, partly due to the fact that the tiny parasympathetic nerve cells are easily damaged by uncontrolled blood glucose levels.

Many ithlete users have reported to us the effects of an extra glass of wine at night on their morning HRV (and perceived wellness!), and the ithlete Team System has been able to identify the odd professional athlete who has not been living such a monk-like existence as they should. A 2014 review study concluded that 0.5g per Kg of bodyweight was unlikely to impact recovery. This translates to five units (two pints of beer/glasses of wine) for an 80Kg athlete but only three units (one large glass of wine) for a 50 Kg person.

Conclusion

In conclusion, by observing the parasympathetic nervous system using HRV measures performed first thing every day, we can keep good tabs on our overall health and longevity prospects. HRV is sensitive to a wide range of acute and chronic diseases, and although not specific to any one condition, using exercise, diet, sleep and stress-reducing activities, you can use HRV to find a lifestyle that works for you, and stand the best chance of becoming and remaining healthier than if you were not monitoring HRV.

References:

Barnes MJ. (2014). Alcohol: impact on sports performance and recovery in male athletes. Retrieved from PubMed

de Sousa, T. L. W. et al. (2019). Dose-response relationship between very vigorous physical activity and cardiovascular health assessed by heart rate variability in adults: Cross-sectional results from the EPIMOV study. Retrieved from PLoS ONE

Grässler, B. et al. (2021). Effects of Different Training Interventions on Heart Rate Variability and Cardiovascular Health and Risk Factors in Young and Middle-Aged Adults: A Systematic Review. Retrieved from Frontiers

Huston, J. M. & Tracey, K. J. (2010). The pulse of inflammation: heart rate variability, the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and implications for therapy. Retrieved from PubMed

Jarczok, M. N. et al. (2015). Investigating the Associations of Self-Rated Health: Heart Rate Variability Is More Strongly Associated than Inflammatory and Other Frequently Used Biomarkers in a Cross-Sectional Occupational Sample. Retrieved from Europe PMC

Jarczok, M.N. et al. (2019). First Evaluation of an Index of Low Vagally-Mediated Heart Rate Variability as a Marker of Health Risks in Human Adults: Proof of Concept. Retrieved from MDPI

Utzinger-Wheeler, M. L. (2007). ‘Enhancing Heart Rate Variability’, in Rakel, D. Integrative Medicine, 4th Edition. Elsevier, chapter 96.

Williams, D. P. et al. (2019). Heart rate variability and inflammation: A meta-analysis of human studies. Retrieved from Research Gate

Young, H. A. & Benton, D. (2018). Heart-rate variability: a biomarker to study the influence of nutrition on physiological and psychological health? Retrieved from PubMed