“One of the painful things about our time is that those who feel certainty are stupid, and those with any imagination and understanding are filled with doubt and indecision.”

–Bertrand Russell

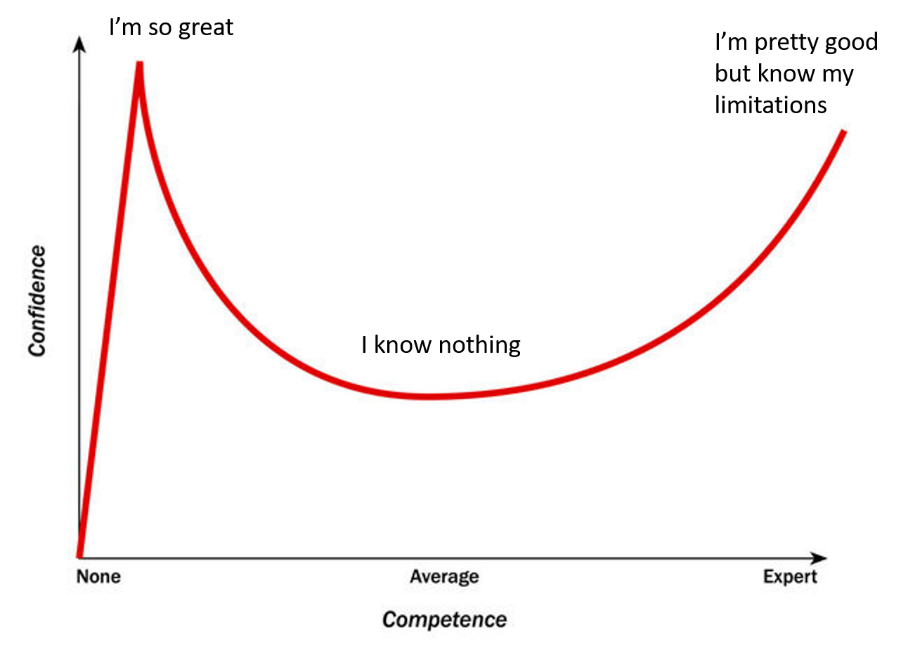

This quote from British philosopher Bertrand Russell describes the Dunning-Kruger effect. This human affliction, based on incomplete or misguided knowledge, leads many coaches and athletes into believing, saying, and doing ridiculous things. The same affliction prevents them from recognizing their own errors and sometimes delighting in the pleasure of highlighting the stupidity of others.

All of us have experienced this zone of delusion. It’s easy to get trapped within it, especially for those who experience high levels of success, independent of their cognitive ability. In this article, I’ll explore the importance of protecting ourselves against getting trapped in the wrong part of the Dunning-Kruger wiggle.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect in Coaching

As a coach, the journey from being a novice to an expert is a challenging one. Only the most committed reach their destination. To do so, the greatest barrier coaches must overcome is an internal one, in recognizing what they don’t know. Failing to clear this barrier usually occurs because of too narrow a conceptualization of performance and how to enhance it. Before you say “he’s talking about someone else”, my academic research tells us that the majority of endurance coaches typically focus on biophysical “stuff” (i.e. focusing on developing the physiological engine through training load prescription). However, human performance is complex and multifactorial, in which as coaches we must consider environmental, social, mental, and sometimes spiritual factors, too. Few ever get close to fully understanding how they all interact together. But, not recognizing the importance of and being able to account for complexity in our decision making suggests a lack of expertise.

Inflated ego and overconfidence are also markers of “stupidity.” The dichotomy is that people are often attracted to and more likely to follow egotistical, confident people as these attributes can be mistaken for leadership qualities. As coaches, we are judged through association with successful athletes, too. If a coach works with one or two high-profile winners, then it’s far more likely that they’ll attract even more. When this happens, that self-confidence and ego will grow at a rate that is often greatly disproportionate to expertise.

Such self-aggrandizing behaviors often result in coaching that is orientated towards overtly tough training regimes, promotion of mental toughness, and anti-intellectualism. It is without doubt that such coaching environments are highly effective for some athletes. However, we rarely hear about the casualties that may have prospered in a more balanced environment. The article written by Chrissie Wellington and myself, Coaching “Race Weight”: A Case Study, is just one example in which others were left to pick up the pieces from such poor coaching.

Even for the most committed coaches, it’s not easy to progress along the Dunning-Kruger wiggle though. The learning journey can be painful, especially when we begin to recognize the limits of our expertise. Egos descend into a pit of despondency and the result is a crisis in confidence. I regularly see this in the coaches I work with on the MSc. in Performance Coaching at the University of Stirling. My job is one in which I challenge coaches to think differently about how they coach by exposing them to different ways of thinking and to other sports. Coaches who show a willingness to change and can accept when they have been wrong tend to prosper. Such change rarely occurs overnight, however. Rather, I often reassure coaches that self-doubt is normal.

The recognition of being wrong also demonstrates that they are on the path to expertise. This path is far rockier for coaches who fail to recognize their biases or learn to provide deeper justification for their coaching beliefs. However, I still have respect for these coaches because they’ve invested time and money to learn to be better. It’s just that their progress is often slower. Coaches with low competence and high-confidence are far less likely to challenge themselves intellectually, believing that they know it all.

Power Dynamics and the Coach-Athlete Relationship

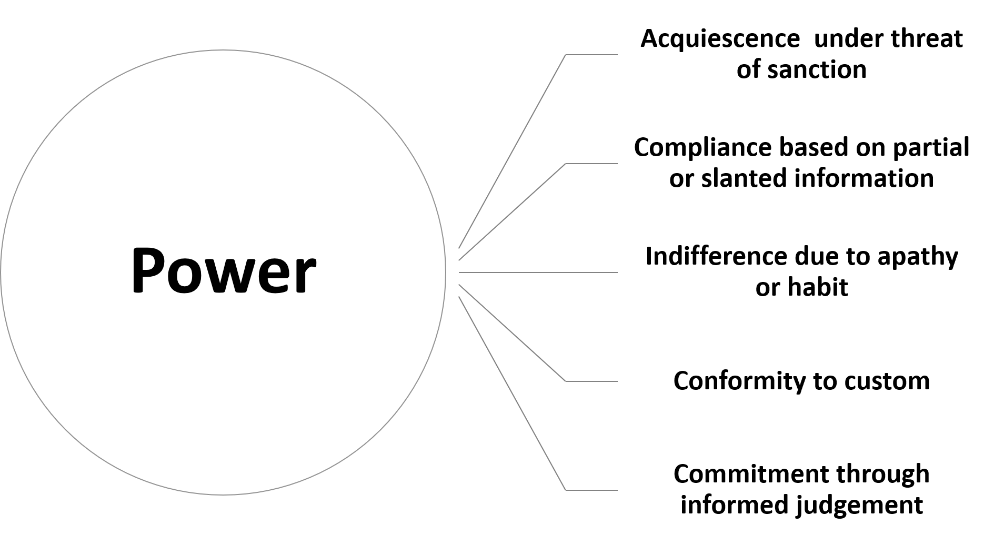

As coaches, our role is to build successful relationships with athletes in which we can positively influence their performance in a process of behavioral change. Power, an often unseen force, is needed to influence the behavior of others and put training plans into effect. While power may be lacking in the vicinity of my bottom bracket, it is always present in relationships involving two or more people. The power consent continuum of David Nyberg is very useful in understanding the power dynamics between coaches and athletes.

Acquiesce under threat of sanction (a.k.a. “do as you are told or else”) is a principle that is important to us all. If we make our living from being a self-employed coach, then we may have to provide the service that an athlete demands, otherwise they’ll stop paying us. Therefore, the balance of power is in favor of the client. Many athletes on federation programs don’t have such power and may not be able to choose who their coach is. They must often do what they’re told on threat (often perceived) of losing their place or funding. Such relationships can work if the program suits the athlete’s personality or if the coach is an agile, adaptable expert. However, cracks will always appear with any coach-athlete relationship where power is out of balance and expertise is lacking.

Compliance based on partial or slanted information means that athletes do what they’re told in the belief that the coach is the expert. The coach is “safe” as long as they are more of an expert than the athletes they coach. However, when an over-confident coach who lacks expertise is found out, they lose credibility very quickly. Athletes leaving a coach en-masse often signal that the coach has been found out. But, because of the Dunning-Kruger effect, the coach will probably blame someone else for their short-comings. In contrast, athlete-client retention rates usually indicate when a coach is doing a great job.

Indifference due to apathy, habit, and conformity to custom are very similar to each other. Everyone muddles along in a sea of complacency without considering the benefits of alternative approaches. This is very common in sport, in which adherence to tradition is common and an almost universal approach to training is adopted. Athletes and coaches often simply adhere to “the system” because that’s just what many humans do for fear of standing out from the crowd. To make matters worse, athletes who become coaches without engaging on a journey of intellectual discovery will usually repeat the same mistakes as their coach. Thus, a cycle of complacency continues between generations.

Idealistically, commitment through informed judgement is best. This means an athlete doing what they are asked to do because they want to. They should have final say about their program and the coach should openly welcome constructive challenge. This approach is dependent on the coach being able to explain the “whys” of their practice, being willing to be wrong, and for the coach-athlete relationship to be relatively free from interference from external powers.

It also means understanding where an athlete is on the Dunning-Kruger wiggle. If the athlete lacks expertise, then they may be unduly influenced by cultural norms or social media posts. The coach who says “I think 15 hours is enough” will likely fall on deaf ears and consent to be coached may be withdrawn if the athlete listens unduly to “what the pros are doing?”.

Additionally, even (or especially) the most intelligent and articulate athletes who understand performance can suffer from exercise addiction. Such addiction is complex, in which athletes may need to satisfy a craving through ever-increasing duration, frequency, and intensity of training despite knowing it can be harmful. A coach whose internal voice is saying “I’m so great” may promote such dangerous behavior with dangerous consequences in terms of athlete health and mental well-being. An expert coach will seek solutions and understand that combatting addiction is slow. That’s why great coaching is messy rather than formulaic. We’ve got to be able to adapt how we coach based on what we face each day and that takes expertise.